“Architecture is a series of successive events that the spirit tries to transmute through the creation of precise and overwhelming relationships that give rise to deep psychological sensations, a spiritual delight is felt by reading the solution, a perception harmony comes to us from the mathematical qualities that combine each element of the project. But how do you get an architectural sensation? With the effect of the relationships that you perceive”

Le Corbusier. The Master of Architectural purism and beton brut. This is how the planning skills of the Swiss architect are usually and correctly summarized. However, it is good to remember that Corbu has not dedicated his life only to this type of project, certainly present and flourishing in the architectural panorama he designed, but he has also strongly deviated by designing something unique and unexpected in relation to his architectural poetics.

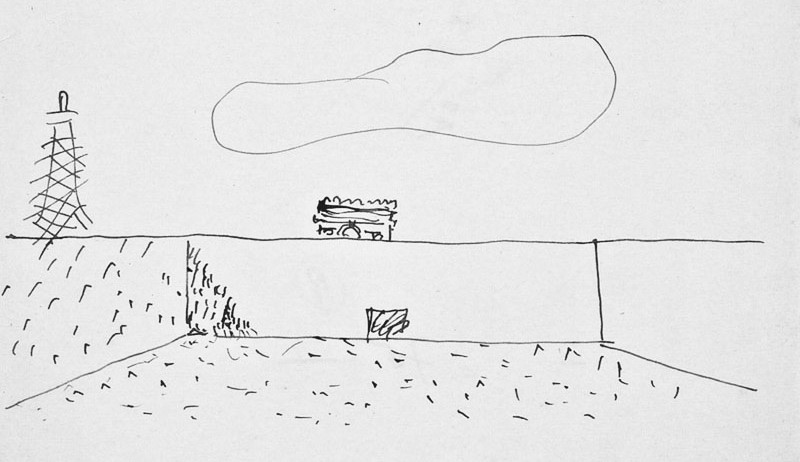

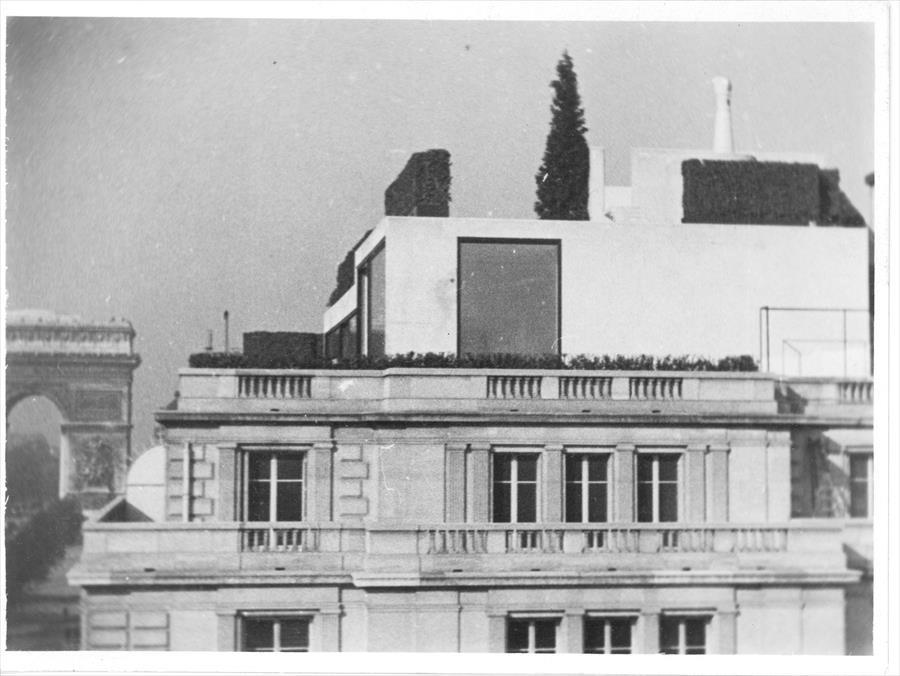

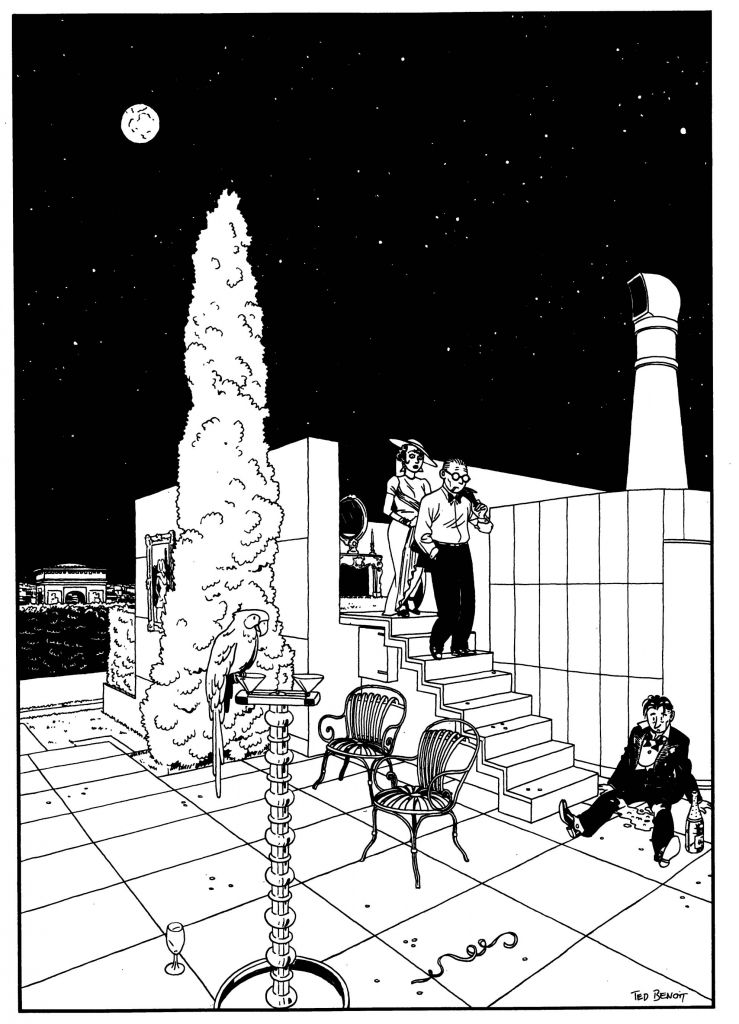

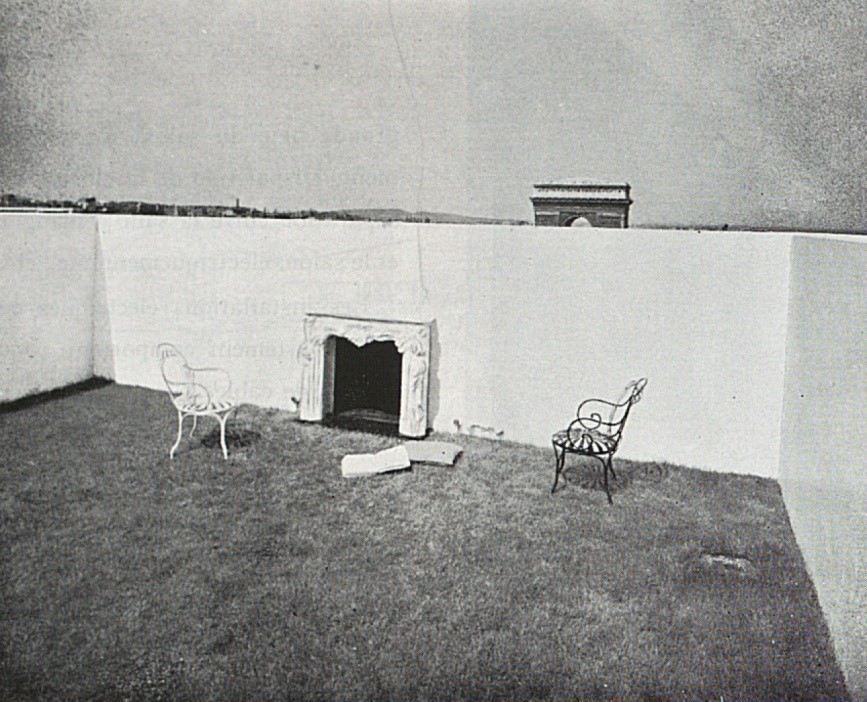

Here, in fact, i twill be possible to explore Le Corbusier in new works, as the protagonist of the design of an eclectic penthouse on the Champs Élysées owned by Carlos de Beistegui, a dècor de fête characterized by a very steep helical staircase where the only handhold was a central handrail of glass spheres, by a darkroom from which, through a periscope, it was possible to see the whole Paris upside down and from a chambre a ciel ouvert which excluded the view of most of the surrounding architectural context, furnished as if it were a small living room with a fireplace, parrots and turf. Characteristics certainly not canonically present in Le Corbusier’s design that we all know and which will probably make turn up the nose to those who consider the architect merely the creator of aseptic white boxes or monstrous interventions characterized by the crudeness of reinforced concrete.

Apart of this, Le Corbusier is often associated with the theme of the promenade architecturale, i.e. a paradigmatic construction that is found in his architecture after 1920, a term that appeared for the first time in 1929, in connection with the unrolling of the views in Villa La Roche. Usually, there is a tendency to reduce this concept only to the spatial experience lived in Villa Savoye, in Maison Ozenfant and in the so-called Villa La Roche, in which it is undeniable that there is a succession of spaces that is strongly studied and based on the continuous change of perspectives.

What is almost never taken into considerations within this rather complex reasoning is the Beistegui Attic, an architectural and artistic jewel unknown to most, even though it represents the highest point of reasoning carried out by Le Corbusier around the concept of promenade architecturale.

What is meant by promenade architecturale? Often this concept as an ascending path within the architectures designed by Le Corbusier but, in doing so, the complexities sought by the architect in his projects are totally canceled. Le Corbusier’s main objective was to push users towards a privileged place where communion with the inner self could be achieved, through a path characterized by a strong and emotional experience, by means of choreographed sequences of spaces that aroused trepidation, wonder and, sometimes, disorientation. When we talk about promenade we are therefore certainly referring to an ascent but not exclusively a physical type: it is above all an emotional experience, characterized by a series of successions that unfold following a sequence of axes and assisted by a succession of different experiences regarding space, textures, light, memories and associations that stitch together to raise the simple peripatetic spatial experience to a narrated aesthetic experience. Le Corusier thus prompted visitors to his projects to use the faculties of memory, analysis and reasoning to appreciate his architecture, understand it and have a completely new experience inside it.

In the experience of a promenade architecturale it is essential to analyze the changes in perspective, the dramatic lights, the use of glass and the precarious ascents, through which Le Corbusier managed to create an incredible sensation of disturbing wonder in the visitors of his architecture. It is precisely for this reason that in Le Corbusier’s architecture there are recurring skylights that dramatically illuminate the space form above making it almost mystical, stairs with small risers and treads sometimes even without a parapet that oblige the visitor to measure every step and, finally, balconies that protrude onto the voids of the atria or outwards, often equipped with slender balustrades that make the experience of looking out precarious and frightened. Therefore, if one ofLe Corbusier’s main purposes was to arouse emotions of wonder, one can only argue that the most fitting architecture for this type of emotional research is the Beistegui penthouse, in which he used unexpected objects and surprise effects, including hedges furniture that allowed the historical presence of the Parisian landscape to be revealed or concealed, turf and a periscope, all elements capable of arousing sensations of amazement in visitors, one of the recurring points of the emotional and spatial experience of the architectural promenade. This certainly happened in the much better-known Maison Ozenfant, Villa Le Roche and Villa Savoye, but it was all present in the Beistegui Attic, where the emotional experience is certainly greater than that of the other three architectures, albeit contemporary.

The eclecticism and particularity of this building can be found in the figure of Carlos de Beistegui, the client of this dècor de fête when, during the Parisian annèes folles, he selected Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret to design a machine à amuser, a penthouse on the Champs-Élysées dedicated entirely to entertaining and hosting crazy Parisian parties typical of those years, characterized by a brilliant and festive atmosphere of cultural and social frenzy in response to the tragic deprivations that Europe had suffered following the outbreak of the Great War, during an enchanted lull between 1920 and the great depression of 1929. With the space having to compete with the spacious villas of other members of the café society, it is no wonder that Beistegui asked Le Corbusier to think outside the box, elevating his concept of the architectural promenade to extremes, to reach a place where awe and marvel were the protagonist.

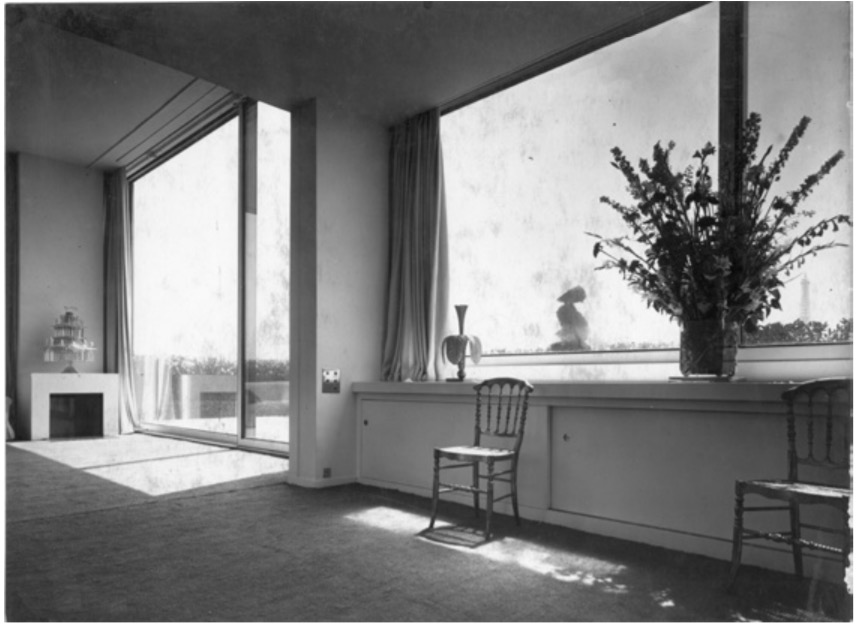

The attic, today unrecognizable, following the partial destruction following the Second World War, was configured on two main levels: the lower one intended to host the portion of a private residence, consisting of kitchen, bathroom, study, bedroom, and a portion intended for parties with living room, dining room and external terraces, and the upper one, determined by three terraces in succession with a difference in height of a few steps between them. Immediately, in the atrium of the attic, the promenade architecturale began where the guest was directed towards the living room through two rectangular skylights that marked the direction to take. Once brought here, the guest was amazed by a mobile chandelier: this, once moved, revealed the view towards the Eiffel Tower and the windows became screens for projecting the films that entertained the café society evenings.

But that was not all: it is easy to imagine at this point Beistegui gathering his guests on the terrace and pressing a button to activate the mobile mechanism of the hedges which, moving, revealed the Arc de Triomphe and the top of the Eiffel Tower, hidden from view until now.

As for the ascension experience, everything revolved around the bizarre spiral staircase located in the center of the ballroom: this one lacked an external handrail and its minimal dimensions forced guests to take a solitary and intimate ascent, where every step had to be carefully weighted. Here the tactile component also came into play: in the center of the staircase there was a pole made up of glass spheres stacked on top of each other, which guests were forced to grip tightly to avoid falling and reach the upper floor.

Once they reached the end of this ascent and therefore landed in the dark room, the body of the guests was once again engaged in the promenade: to have a complete view of Paris, they had to move around the table on which Paris was projected, visible upside down through the use of a periscope.

Leaving this narrow and gloomy place, the guests were catapulted into the light of the intermediate terrace, characterized by white marbles that reflected the light and dazzled them, having to take a few seconds to get used to the natural light.

From here it was possible to go down a few steps towards the lower terrace, where once again the view towards the Arc de Triomphe was blocked by a new set of shrubs, or to go up towards an ambiguous place with a mysterious exterior introduced by a further staircase without a handrail, fascinating in its precariousness.

Thus we reached the end of the promenade, in the chambre à ciel ouvert, an open-air room, lacking a roof, characterized by grass paving and high perimeter walls, which allowed to admire only the tip of the Eiffel Tower and the top part of the Arc de Triomphe. This was the least invasive application of the principle of Plan Voisin, in which Le Corusier had prescribed the clean slate of large areas of Paris except for the great historical presences, including the tower and the arc. Here it is easy to imagine Beistegui’s guests amazed by the view of the sky as they walked barefoot immersed in their thoughts, accompanied by the chirping of the parrots that Beistegui had placed here, separated from the other rooms of the dècor de fête and, conceptually, from the Parisian chaos through a very heavy door that made the room a separate and distinct environment from everything that happened outside.

What took shape in this architecture was therefore an ascending path that led, passing through eclectic and bizarre spaces, towards a privileged place that prompted introspection and communion with one’s self.

In conclusion, the Beistegui’s penthouse was not just a dècor de fête, a banal penthouse for parties, but it was a place to have a strong emotional experience, possible thanks to the promenade architecturale and all the para-architectural stratagems devised by Le Corbusier in collaboration with Beistegui. This allowed guests to concentrate on the ascent they were traveling, always on the alert waiting to be amazed by the next element of wonder, before concluding their experience in an intimate and privileged place. Thanks to these intrinsic characteristics of this architecture, including the direction of life through lights and views, mostly denied and hidden, precarious experiences and generators of strong amazement that engaged the entire body and all the sense, the Beistegui penthouse stands as the progenitor of the architecture designed by Le Corbusier based on the spiritual concept of promenade architecturale. The penthouse thus surpasses without hesitation or fear the experiences inside, and sometimes outside, of the other already mentioned architectures usually described centered around the promenade architecturale, certainly based on the emotional and evocative ascent of the space, but where the disturbing marvel so chased by Le Corbusier does not have the same tenor as that experienced inside the Parisian penthouse on the Champs Élysées.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Alioscia Mozzato, The Image of the City and the Rhetoric of the Oxymoron. Le Corbusier and the Apartment of Charles de Beistegui, 2019.

- Le Corbusier, Appartement avec terrasse, avenue des Champs-Elysèes, à Paris (1932), «Architecte», 10.

- Paolo Melis, Memoria M Memoria. L’attico Beistegui di Le Corbusier e Pierre Jeanneret, «Controspazio», settembre 1977, pp. 32-37.

- Ross Anderson, All of Paris, Darkly: Le Corbusier’s Beistegui Apartment, 1929-1931, Valencia 2015, pp. 113-127.

- Wim Van Den Bergh, Charles de Beistegui. Autobiography and Patronage, «OASE #83», 2010.

- Wim Van Den Bergh, Beistegui avant Le Corbusier. Genèse du penthouse des Champs-Elysées, Editions B2, Paris 2015.

- Sur les toits de Paris. Le jardin enchantè de Beistegui, «Vogue», ottobre 1932, pp. 54-55, 74.

- Champs elysées: Modern boulevard, «Vogue», 15 luglio 1933, pp. 13-14.

- Parisian penthouse, «Vogue», 82, 15 dicembre 1933, pp. 46-47.

- A high stepping party, near Paris, at Don Carlos de Beistegui’s, «Vogue», settembre 1965, pp. 182-183.

- Sur les toits de Paris. Le jardin enchantè de Beistegui, «Vogue», ottobre 1932, p. 54.

IMAGE CREDITS

All the photos are form the Fondation Le Corbusier, with the exception of n. 2, an illustration by Ted Benoit, and n. 5, coming from www.veniceartguide.it.