The city, and on a smaller scale the neighborhood, are conceived by the designers as places capable of allowing connections, intensifying exchanges between human beings and having aggregations as the final goal, in order to achieve the success of an architectural or urban intervention.

Streets, squares, parks and any other kind of interstitial space between houses are identified as the ideal space for creating bonds.

The “Machine for Living In”, as Le Corbusier defines the house, is that place which has the task of protecting a person from external dangers, being the background of his actions, the environment in which the essence of each individual can express itself.

Definition that, nowadays, should be adapted to the new paradigms of contemporary social life.

Broadening the concept, the house should include all spaces, both external and therefore not only between walls and attics, as they’re vital for carrying out daily activities, and complete the daily cycle of social interactions.

As the anthropologist Francesco Remotti writes, “living is a tiring compromise between the need for intimacy and sharing and the need of opening up to the outside world; a point of precarious balance between closure and openness, between recollections in the intimacy of a “We” or an “I” and opening up to the social relationship.” [Staid, 2017, p. 20]

A closer look

Taking the previous premises into account, the attention is drawn to all those problematic neighborhoods, built in the last century, in which the principle that led to their construction resulted in a pressing process of socio-cultural and architectural degradation.

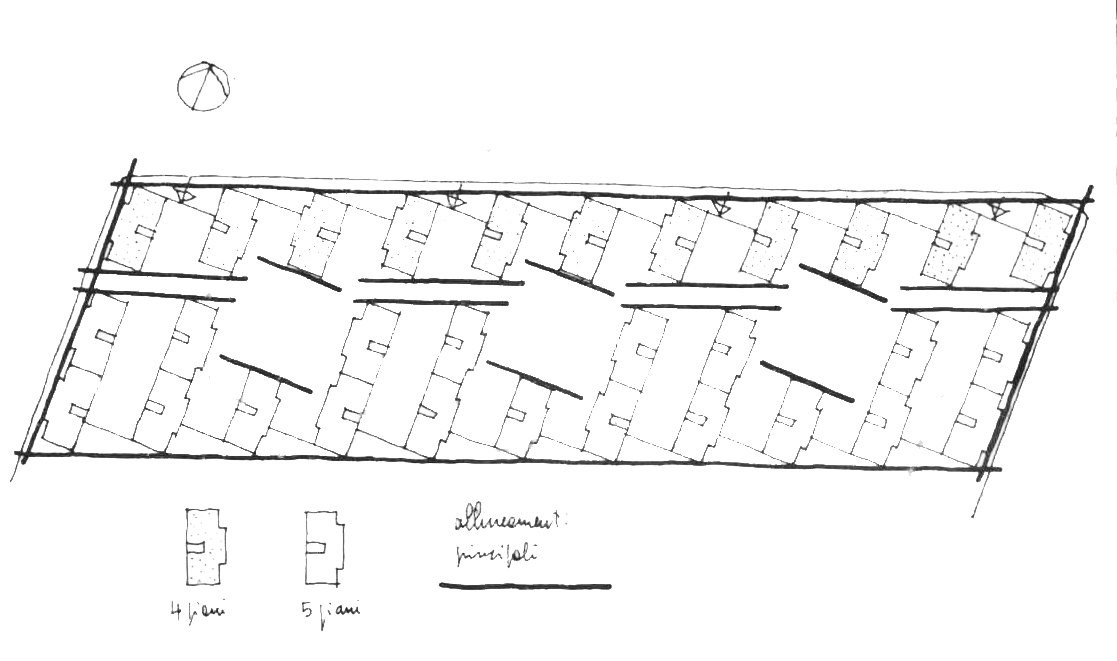

This is the case of the Gabriele D’Annunzio district, a lot belonging to the San Siro area (Milan), built in the years 1938-41 on Franco Albini, Renato Camus and Giancarlo Palanti’s project, commissioned by the Istituto Fascista Autonomo Case Popolari of Milan, in line with the request of that precise historical moment.

The area, an exemplary element of a much larger whole, presents numerous problems related to the inexorable change that has taken place over the years.

Therefore, the resolution of these critical aspects through a radical design intervention is increasingly necessary, that acts in contrast with the context, modifying the existing schemes, “the forms [which] must be compatible for the functions, which must offer spaces conducive to responding to new needs.” [Belgiojoso, 1986].

In this way, the axioms of society hopefully will be changed by modifying the paradigms of architecture.

The latter plays the role of dictator of rules that set human movements, such as theater for the actor.

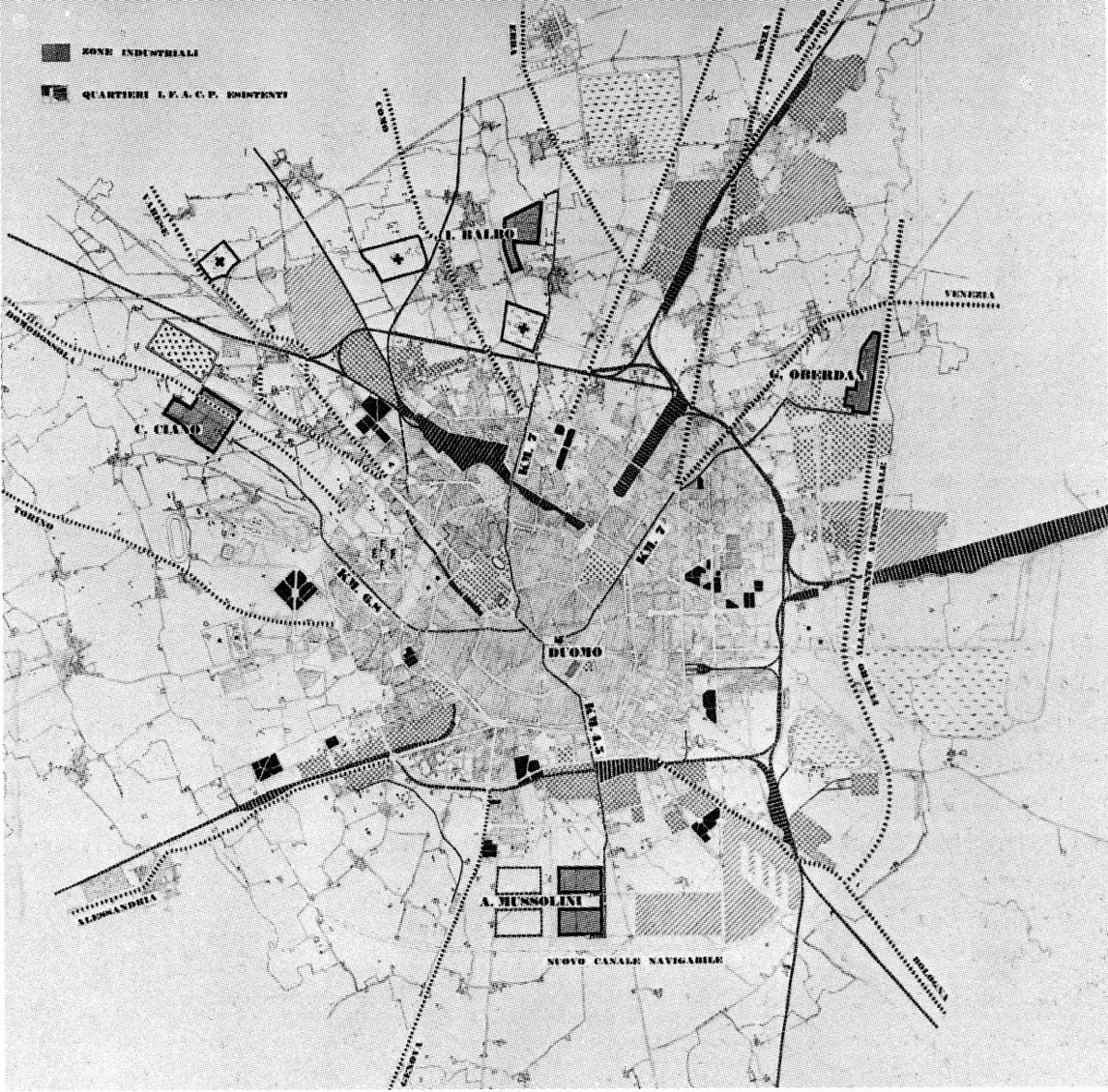

The positioning of the four neighborhoods in the surroundings of Milan

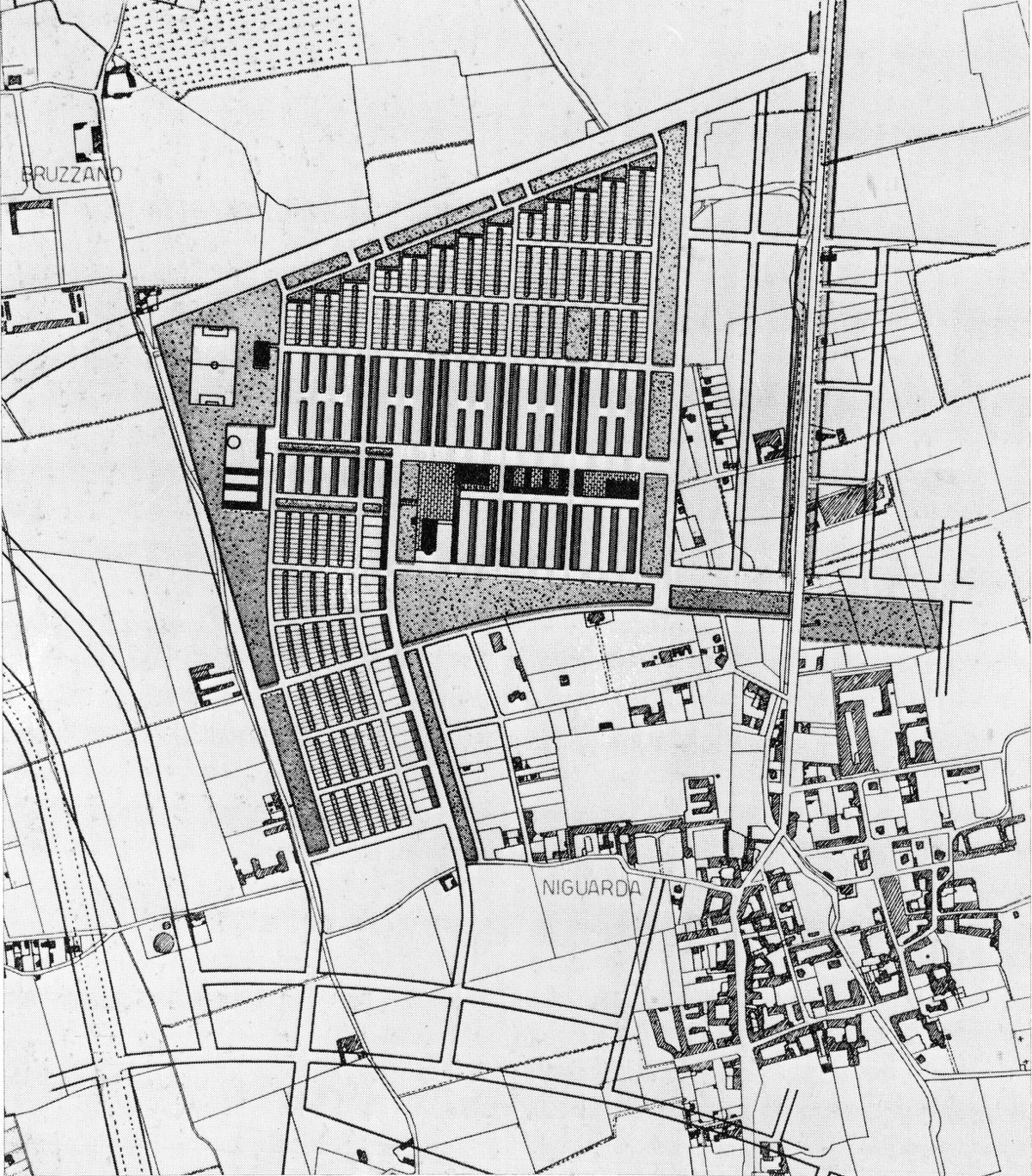

Italo Balbo neighborhood, master plan

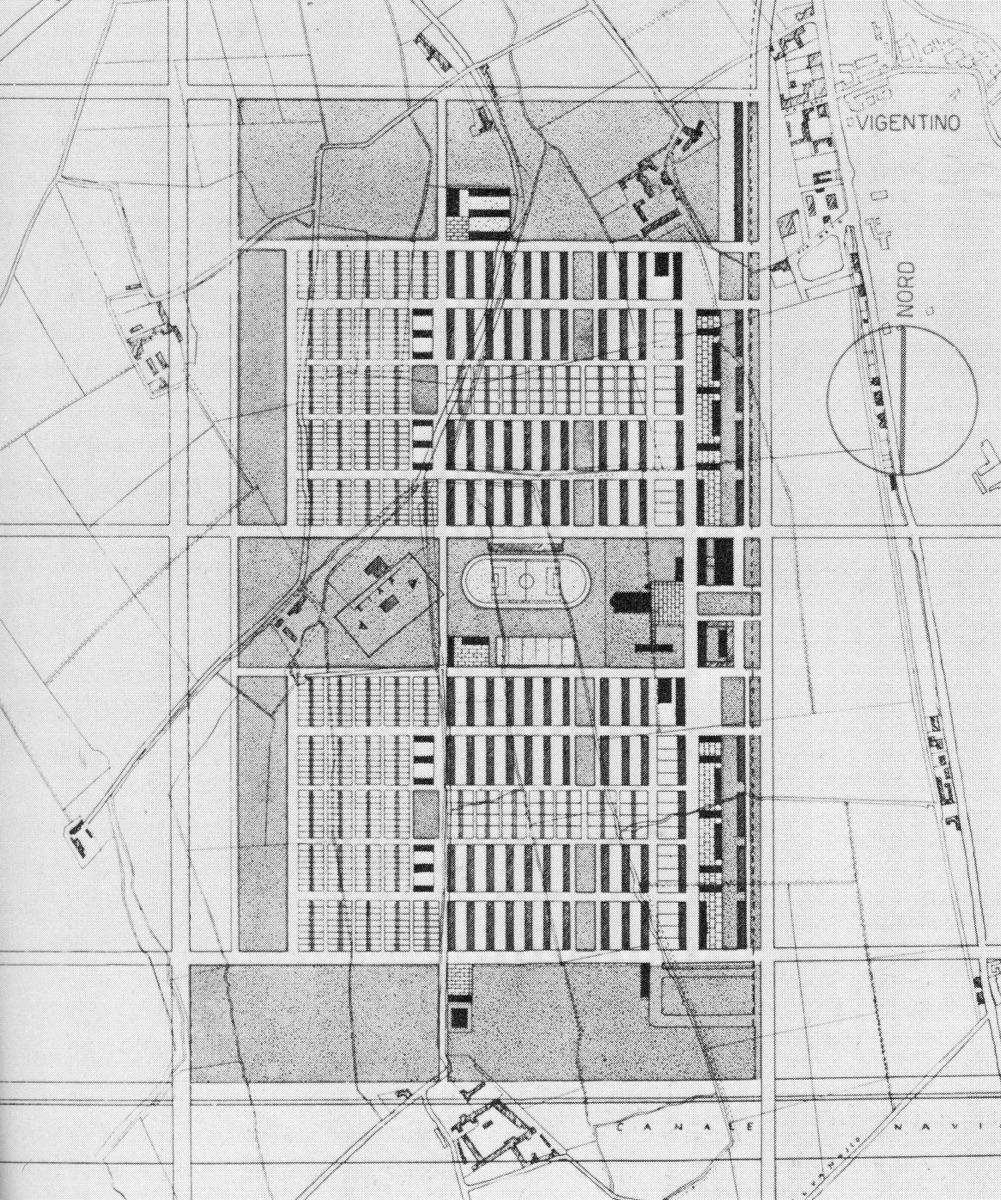

Arnaldo Mussolini neighborhood, master plan

Guglielmo Oberdan neighborhood, master plan

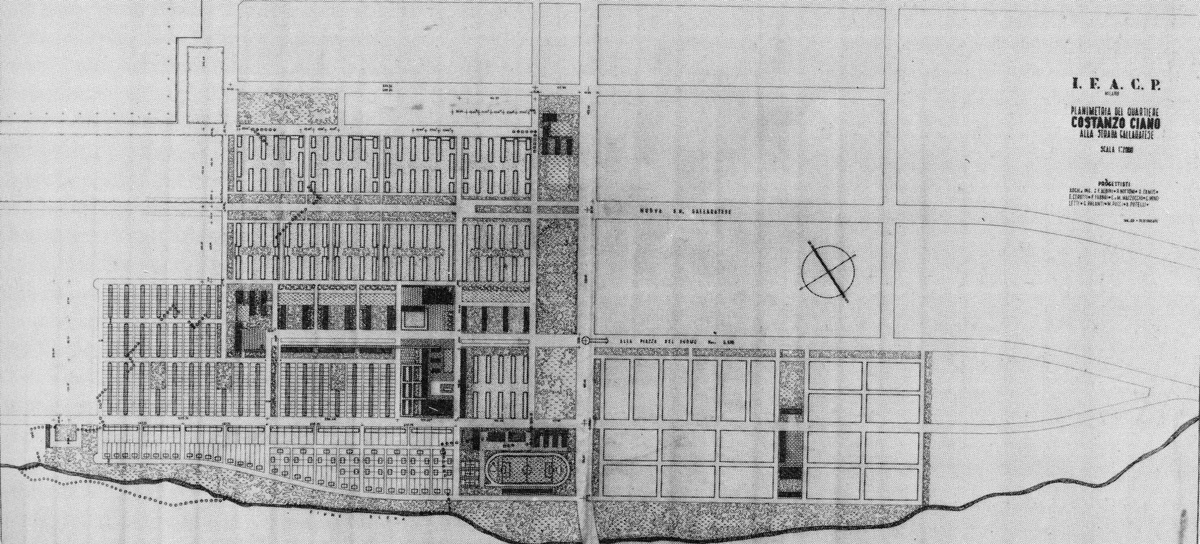

Costanzo Ciano neighborhood (II version), master plan

Specifically, when dealing with such fragile areas we are talking about “suburban” areas, or at least such when they were created and their close relationship-contrast with the city center, highlighting two main characteristics: physical aspect of the place and socio-cultural.

It is therefore relevant to analyze the word “integration” which has a double value:

due to the present heterogeneity of the inhabitants (by social, economic, cultural condition) it would have the potential to create a lively place of exchange and growth;

at the same time if we speak of the “perception of integration” the character automatically assumes a negative meaning, thus defining a real antithesis in the word itself.

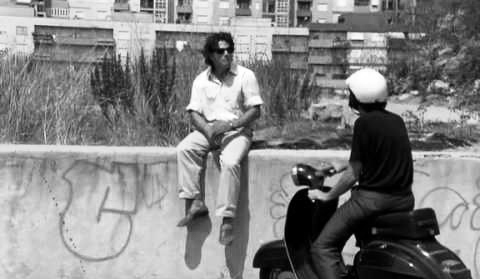

Direct experience: a morning at San Siro

The visit to the neighborhood generated a strong impression, which gave rise to some design ideas and intentions.

There is an almost insurmountable limit, both physically and socially constituted above all by the result of public opinion towards this neighborhood. Nanni Moretti also tells it in a scene from the film “Dear Diary” through an exchange of jokes: he notices that the Spinaceto district (located in Rome) does not appear as it was told to him.

Frames from the film “Dear Diary,” Nanni Moretti, 1993

The fences, the closed loggias, the empty streets, the parked cars that create a second wall, take the observer into a surreal dimension: it seems to observe a different town, a city within the city, not the Milan in the collective imagination, or at least not the one advertised.

The following concept encloses the photograph that is taken through our eyes:

“Like leprosy, the plague and smallpox, the fear of the poor, of the foreigner, of the nomad, of the different has often given rise to the request for specific policies of exclusion, control, expulsion or internment, which most often have led also to the obsessive search and stigmatization of certain social group”.

[Secchi 2013, p.21]

Stigma becomes superior to a sharing policy. The policy of polarization of the new neighborhoods, of their functional specific, has made easier, perhaps unintentionally, the current condition of social decay.

In this way the political and social context of the first four decades of the twentieth century is identified. Production in the construction field undergoes a significant increase, we are witnessing an exponential growth in the construction of buildings.

In this period, one way to be able to practice architecture, to be able to change the layout of a city, was represented by the competitions organized by the IFACP. Among the many, Franco Albini, Renato Camus and Giancarlo Palanti took care of the Fabio Filzi, Ettore Ponti and Gabriele D’Annunzio neighborhoods; the latter one of a much larger area, divided into two quadrants (Quartiere Milite Ignoto and Quartiere Baracca).

As the different applications to the various urban interventions’ sites, a general theoretical method takes root to be used as a manual of aesthetic and functional rules, to guarantee the minimum standards of form and habitability.

However, today these elements are critical due to emerging issues that doesn’t meet today’s standards.

With the evolution of society and the consequent overcoming of some mode of conceiving the home, these paradigms have exhausted themselves in situations of threat to social life. Architecture does not correspond to the evolution of society, which requires continuous updates, alignment policies with contemporary standards, due to the change in the way of life.

Precisely, these neighborhoods are made up of a private space (houses that today are too narrow to be lived in), and a collective space that should facilitate the sharing of moments of daily life and promote knowledge of the cultural background of the neighborhood.

It would be appropriate to emphasize the equal relationship between housing units and urban space as sides of the same coin.

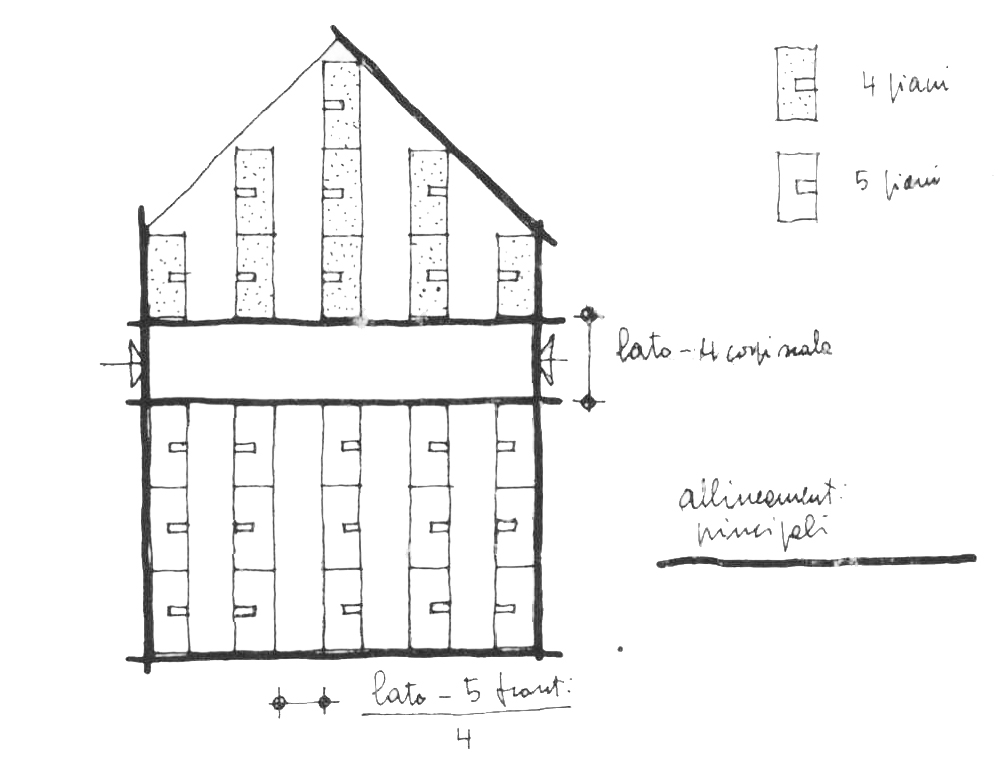

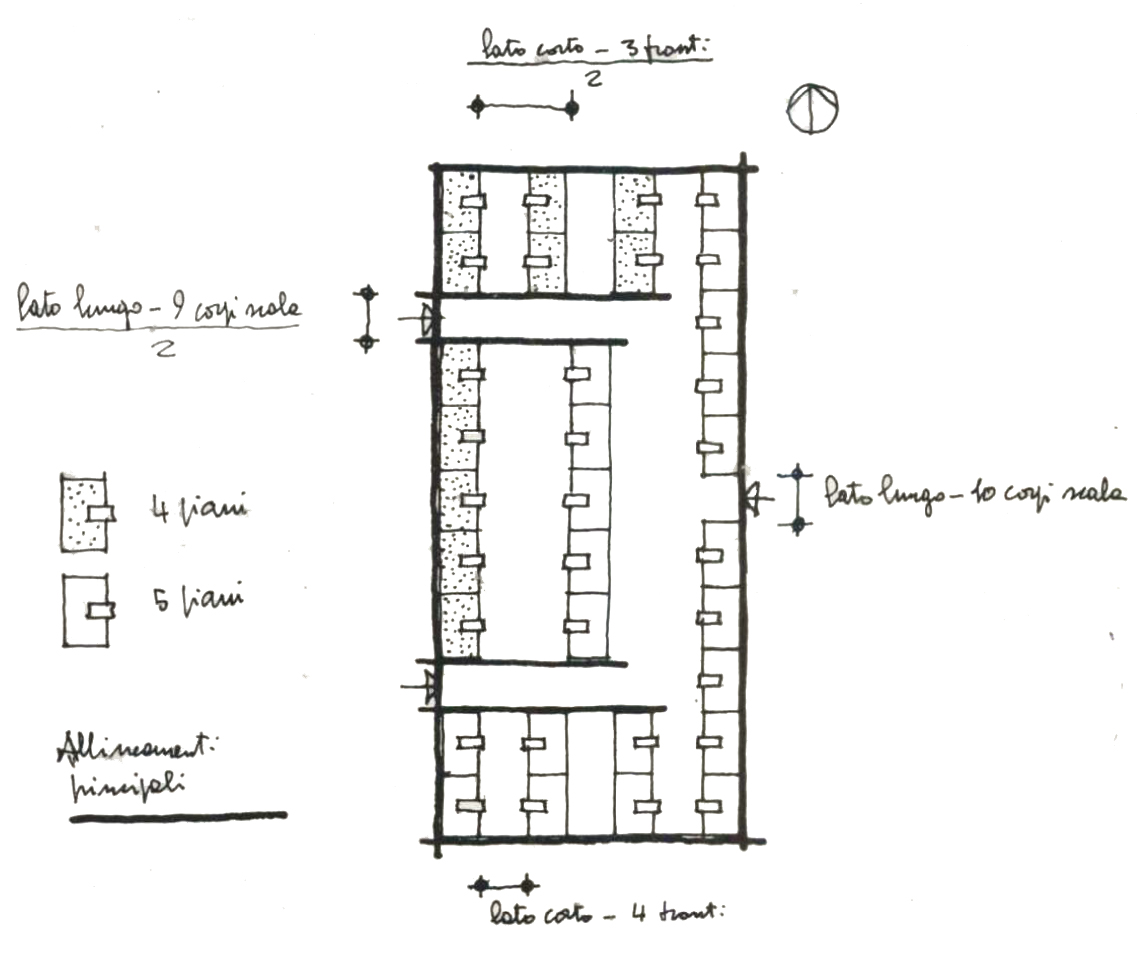

Floor plans of the Gabriele D’annunzio, Fabio Filzi, Ettore Ponti neighborhoods.

Current photos of the Gabriele D’annunzio district

The link between prefabrication and way of life

To better understand the phenomenon of massive building that has taken place in Italy since the beginning of the 20th century, it is useful to deepen the study through the ethnography of populations living on the margins in the West, in the rest of the European continent and in the world. They share a precarious socio-economic condition, which drives people to seek a solution that fits their needs, starting from the request to have a private space, which can defend them from the outside.

The rationalist component, in Italy and abroad, guides the building production of this period, formed by general characteristics such as the prefabrication of materials, the mass production of structural components, the rooted use of reinforced concrete.

In Germany, from 1949 to 1958, there was a massive production of apartments and social housing (about four and a half million units), driven by the post-war economic recovery. The result was a urban expansion of great impact with housing that are differentiated according to the socio-economic status of the user.

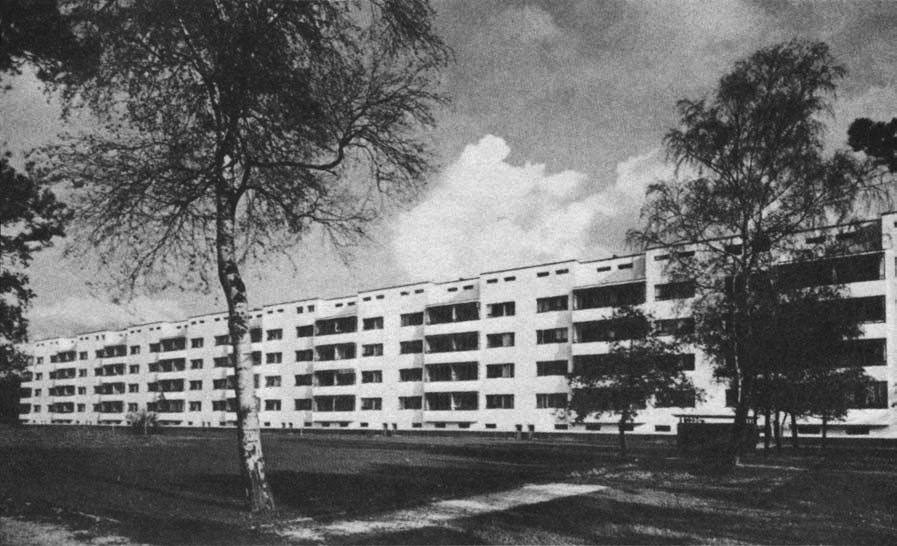

The Siedlung defined the new suburbs of Germany in the first decades of the 1900s, based on the principle of the Existenzminimum, optimizing the surface of the soil used and improving solar exposure and the ventilation method. Examples are the Weissenhof in Stuttgart (1927) and the Siemensstadt in Berlin (1930).

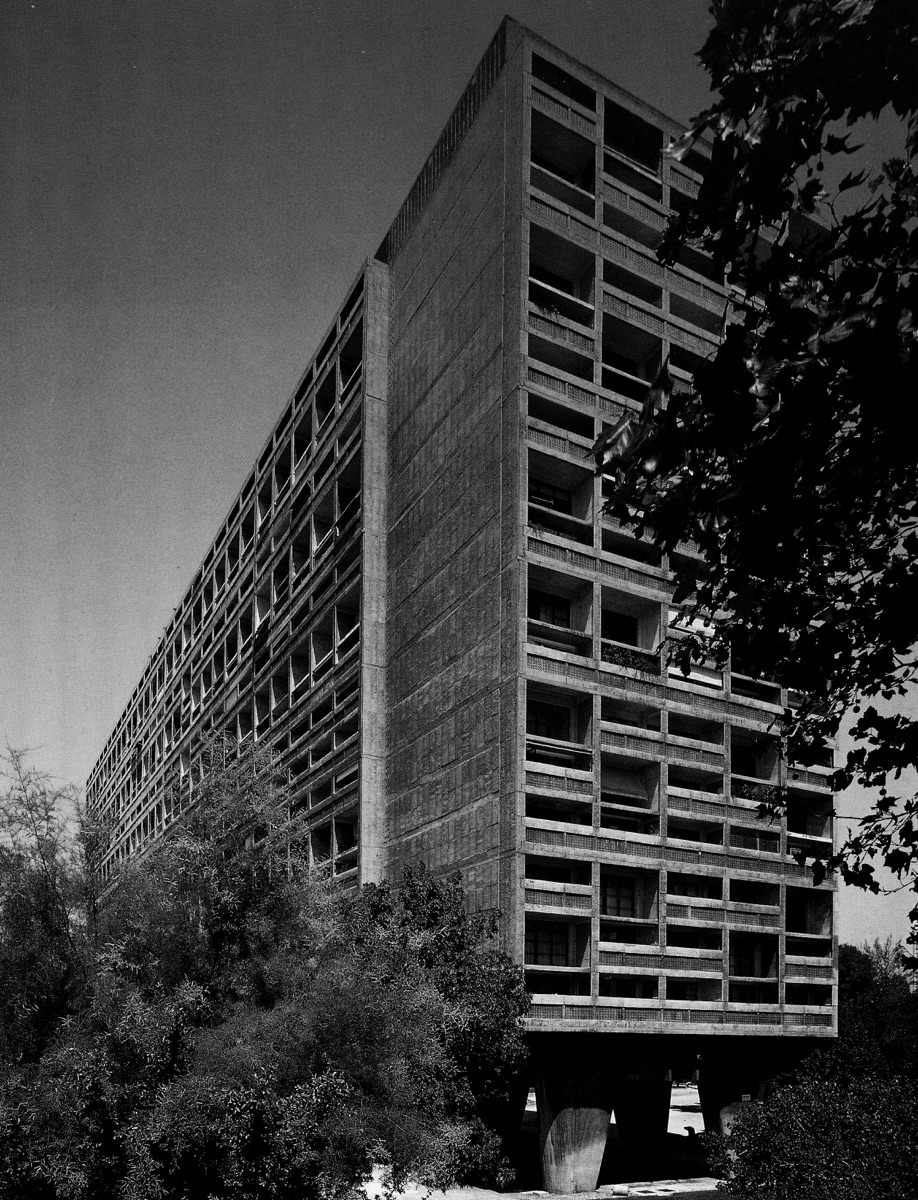

The German capital was also home to several examples of brutalist-style social housing, including Le Corbusier’s “typical Berlin”. Similar to the other Unité d’Habitation of the same type (Marseilles 1947-1952), it houses 530 apartments on 17 floors, but it fails to satisfy the high demand for housing (there were 3500 applications).

Also in France, where the use of prefabrication began in the late 1800s and modernization theories were accelerated to reduce the huge manpower required by urban development, we are witnessing an expansion of the city, beyond the historical center in the so-called Parisian “Banlieue”, also made up of buildings of extraordinary engineering research.

Like every other European nation, Finland has also had to face its housing problem that was born with population growth and the mass influx from the countryside to the industrial centers.

In this case, climate change must be considered into building progress for minimize the discomfort of the temperature range that characterizes the Finnish climate.

Looking at a non-European context, in Israel there has been a construction of the entire country, from the foundations, from basic services, since this nation was born from the meeting of Jewish people from different parts of the world.

Siemensstadt, Berlin, archive photo

Weissenhof, Stuttgart, archive photo

Given the recent history of the country, the decade between 1934 and 1944 witnessed and expansion of the city of Tel Aviv by immigrants who had lived in Nazi Germany, fleeing overseas for religious reasons. Their cultural background favors the Bauhaus style of housing construction.

However, the consistent and continuous problem of the lack of housing led to an acceleration of construction times, leading to a preference for public over private construction. Over 70% of the country’s housing was built between 1949 and 1960.

The method of responding to the population growth of cities is different in the United States. An exemplary case is Washington, which with the “2000 Plan” provides for the establishment of twenty satellite cities, which will improve the living conditions of the inhabitants, removing them from the unhealthy living conditions of the suburbs. Every satellite city (the first was Reston) establishes a relationship of coexistence with the green system.

The vegetation is therefore entrusted with the task of improving the image of the city and the perception of the living context by users.

Unitè d’habitation in Marseille as seen from the southeast.

Nanterre neighborhood (northwest of Paris), consisting of 700 apartments

It is therefore possible to detect the common factors and the main solutions adopted in various countries of the world which, in the twentieth century, found themselves facing a serious problem of housing shortage, due the massive movement of the population towards the cities (production centers).

However, this type of problem still exists in contemporary times, evolving into other formal typologies.

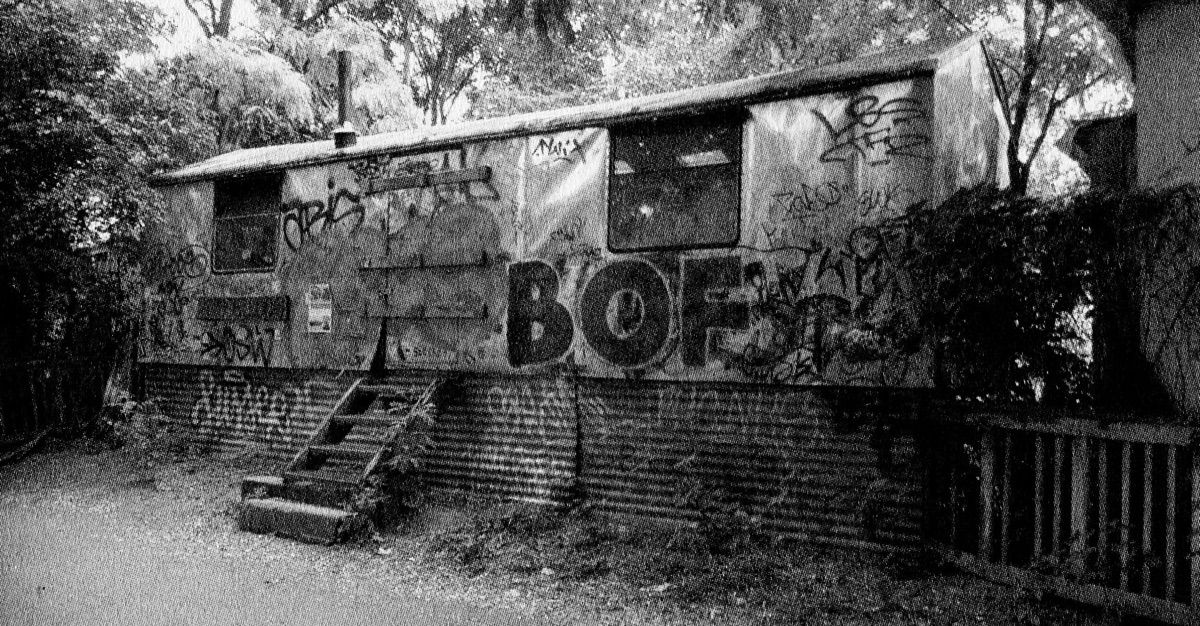

Unfortunately, despite being identifiable as a primary right of the human being, housing is not possessed by many. The resulting response is the appropriation of space in an informal way, the construction of an environment in which someone can identify himself.

Phenomena of squatting, the desire to redeem one’s dignity are the founding principles of these process that produce alternative life forms.

In Italy we are witnessing the formation of self-managed villages, Municipalities characterized by a strong sense of community; abroad, there are the corresponding Wagenplatz or ecovillages, based on respect for the environment.

Wagenplatz, Germany

Wagenburg, Lohmühnlestraße, Berlin

Portrait of life on the street, Berlin

Wagenburg, Lohmühnlestraße, Berlin

The dynamism of the binomial “architecture-society”

We are used to calling “home” that place formed by a door to open, a room to cross, a window facing outwards. In recent times, this concept has been overcome, better identified with a comfort zone, a place that is not always recognizable in a building, but a place in which “one can feel at home”.

With the progress of the globalization, and therefore with the encounter between cultures through social relations, we are witnessing a proliferation of interactions, a different way of conceiving spaces.

For a child, the house can be the playground where play with friends, for an elderly lady the bench where she spends time observing. But those are not only simple actions, are ways of experiencing a place, the surrounding environment.

It is also visible in American urban planning, where the major highways cut off the suburbs inhabited mostly by ethnic minorities outside the city, where a certain morphological fabric tries to control social connections, sometimes by adapting to the designed spaces, sometimes by breaking the mold with grafts in informal places.

Urgent action is needed for trying to formalize these spaces, to recognize them. In fact, the formal language is no longer suitable for satisfying certain needs: the result is the evolution of social forms and, at the same time, the interruption of development of the context, leading the system to failure.

It is in human nature to define themselves through relationships with other individual, consequently transforming the reality that surrounds them, going through a process of renewal contemporary to the architectural one.

We refer to given structures and subvert them.

The architect, moreover, performs actions of great importance. It defines, separates, distances, unites, opens up, sizes, specifies a place, gives it an identity. But this identity will always be fictitious, not corresponding in its entirety to reality, because it lacks the last and most important piece: the dynamic factor of society.

Consequently, architecture has the delicate function of redeeming a place, of freeing it from its superstructures. It becomes a means of expression of the place itself, a way through which society is linked to a specific historical period, an “element of progress, service and cultural strength” to “obtain an improvement in living conditions and greater cultural freedom”.

[Gambirasio 1990, p. 14].

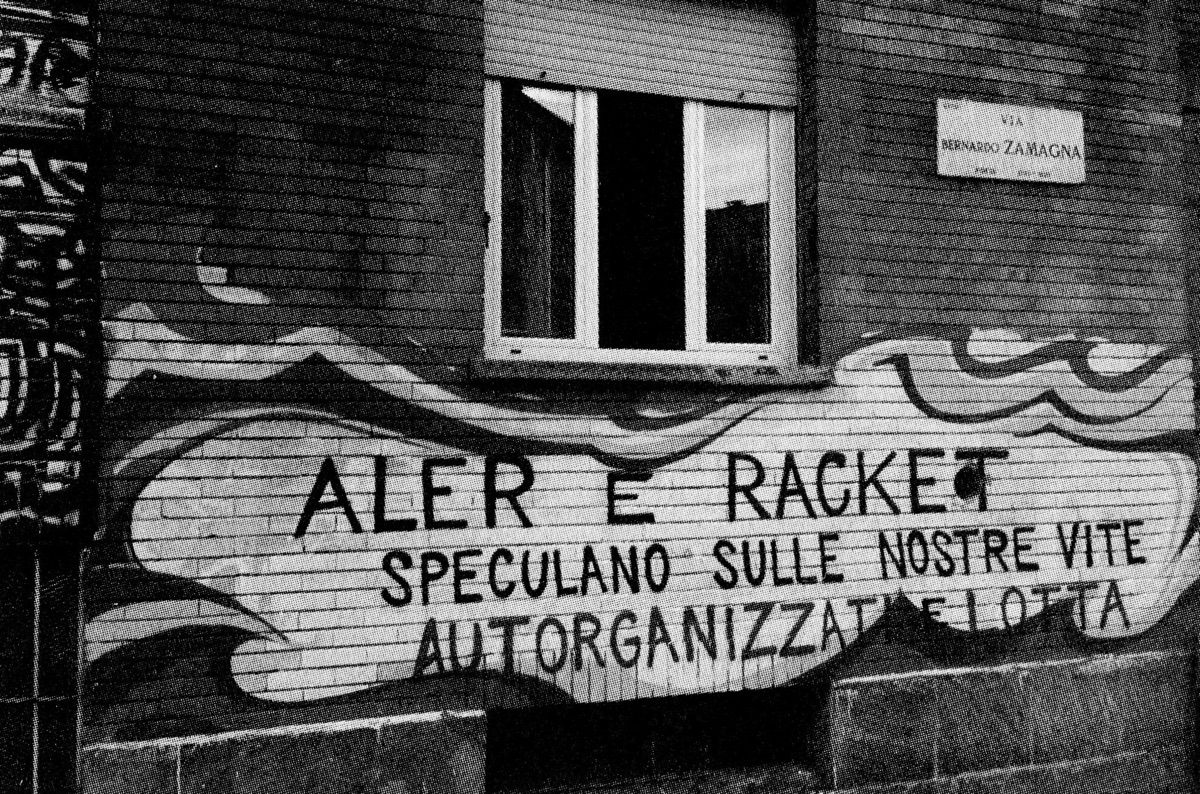

House occupied in Milan

Hausbesetzer Newspaper

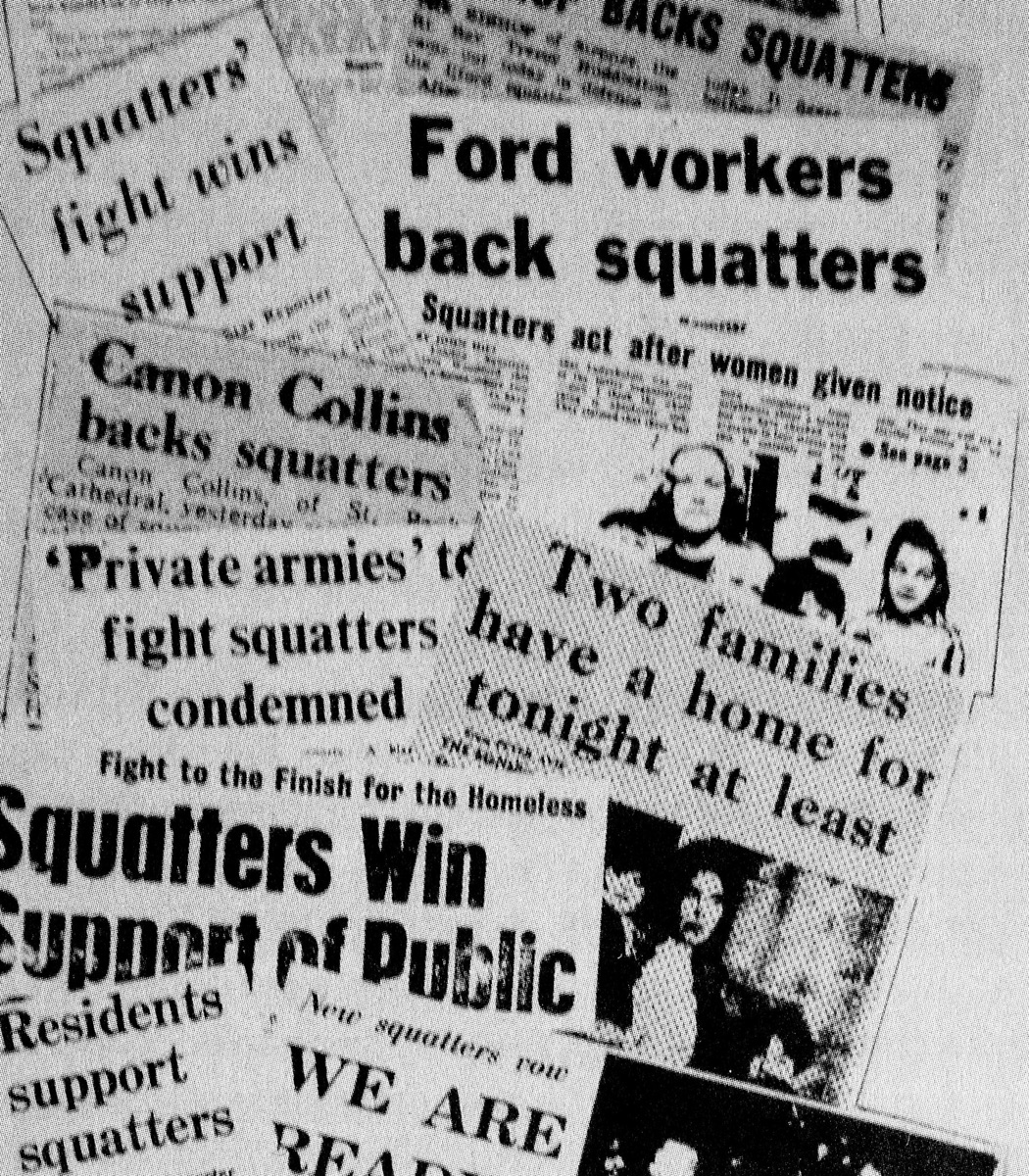

English press on the movements of squatters

Walls of the Ticinese district, Milan

The popular neighborhoods were born at a time when sensitivity towards these issues suffered in favor of the political regime. The affirmation of individuality, the variety of personalities did not find broad consensus, giving, rise to a policy of suppression which led over the decades to an evident rift between architectural forms and communities. The manifestation of the rigor of the rationalist period, through the affirmation of absolute forms, poured into a consequent socio-cultural degradation. Therefore, it is not in the essence of architecture to resolve itself into complete forms.

It is the duty of posterity to remedy, or at least continue a policy of updating the architecture-society system.

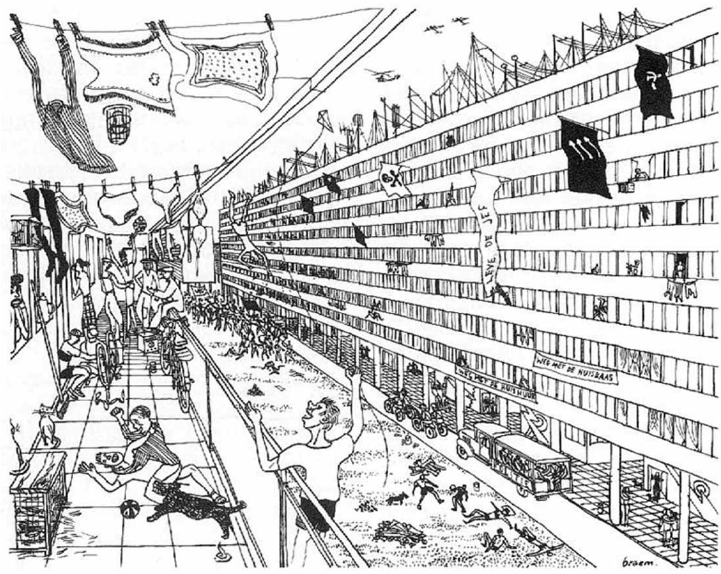

Illustration by Renaat Braem on the perception of social reality.

Bibliographical references

– AIRE (edited by), Ferri P. (in collaboration with), Recupero di quartieri storici di Milano, Società Editrice Edilizia Popolare, Milano 1993

– Bazzanella L., Giammarco C., Progettare le periferie, Celid, Torino ottobre 1986

– Belgiojoso L., Pandakovich D., Marco Albini – Franca Helg – Antonio Piva. Architettura E Design 1970 – 1986, Mondadori, Milano 1986

– Caniggia R., Maffei G. L., Composizione architettonica e tipologia edilizia, Il progetto nell’edilizia di base, Marsilio Editori, Venezia 1984

– Caniggia R., Maffei G. L., Lettura dell’edilizia di base, Marsilio Editori, Venezia 1995

– Cerasi, M., Lo spazio collettivo della città: costruzione e dissoluzione del sistema pubblico nell’architettura della città moderna, preface by Ludovico Quaroni, Gabriele Mazzotta Editore, Milano 1979

– Cognetti F., Padovani L., Perchè (ancora) i quartieri pubblici. Un laboratorio di politiche per la casa, FrancoAngeli – Collana del DAStU, Politecnico di Milano, Milano 2018

– DAStU, Territorio n. 71, FrancoAngeli, Politecnico di Milano 2014, pp.67 – 120, 130 – 133

– Grandi M., Pracchi A., Guida all’architettura moderna, expanded edition on reproduction of the volume published by Zanichelli, nov 1980, Milano 2008

– Guiducci R., Periferie tra degrado e riqualificazione, Bianchi E., Perussia F., Scramaglia R., Scotti M. (in collaboration with), FrancoAngeli s.r.l., Milano 1991

– LeGates R. T., Stout F., The City reader, First published in 1996, Fourth edition, Routledge, Abingdon 2007

– Pagano G., Costruzioni – Casabella, n. 178, anno XV, ottobre 1942

– Pugliese R. (edited by), La casa popolare in Lombardia 1903 – 2003, Edizioni Unicopli, Milano 2005, pp. 102, 103, 106, 107

– Secchi B., La città dei ricchi e la città dei poveri, Editori Laterza, Bari 2013

– Staid A., Abitare illegale,