Architecture, and all its superstructures, is not only a means to exploit space and meet the needs of shelter but also something more. It is a continuous drawing of human living, or a design of the man’s constant need to live in the places, whether natural or artificial, which are always reproduction, description of the very first place.

The house is above all an anthropological place, a place inhabited by man that is not just a “staying”, but first of all a “being”.

The spaces we live change and evolve with the same speed as we do so, they are a continuous reflection of our person. The mutability of our soul, our aspirations and hopes, our values: all this continually affects spaces we coexist with. The form is meaning. The form is essence.

When we build we do but detach a convenient quantity of space, seclude it and protect it, and all architecture springs from that necessity.

Geoffrey Scott, 1914

Necessity. It seems that man, after all, lives or even better, survives, thanks to his innate sense of self-protection.

Building is the most immediate and effective way he knows to do it: working on the three dimensions he fances off spaces, enclosing places that he thinks he has generated but that are actually extrapolated from nature and its relationship.

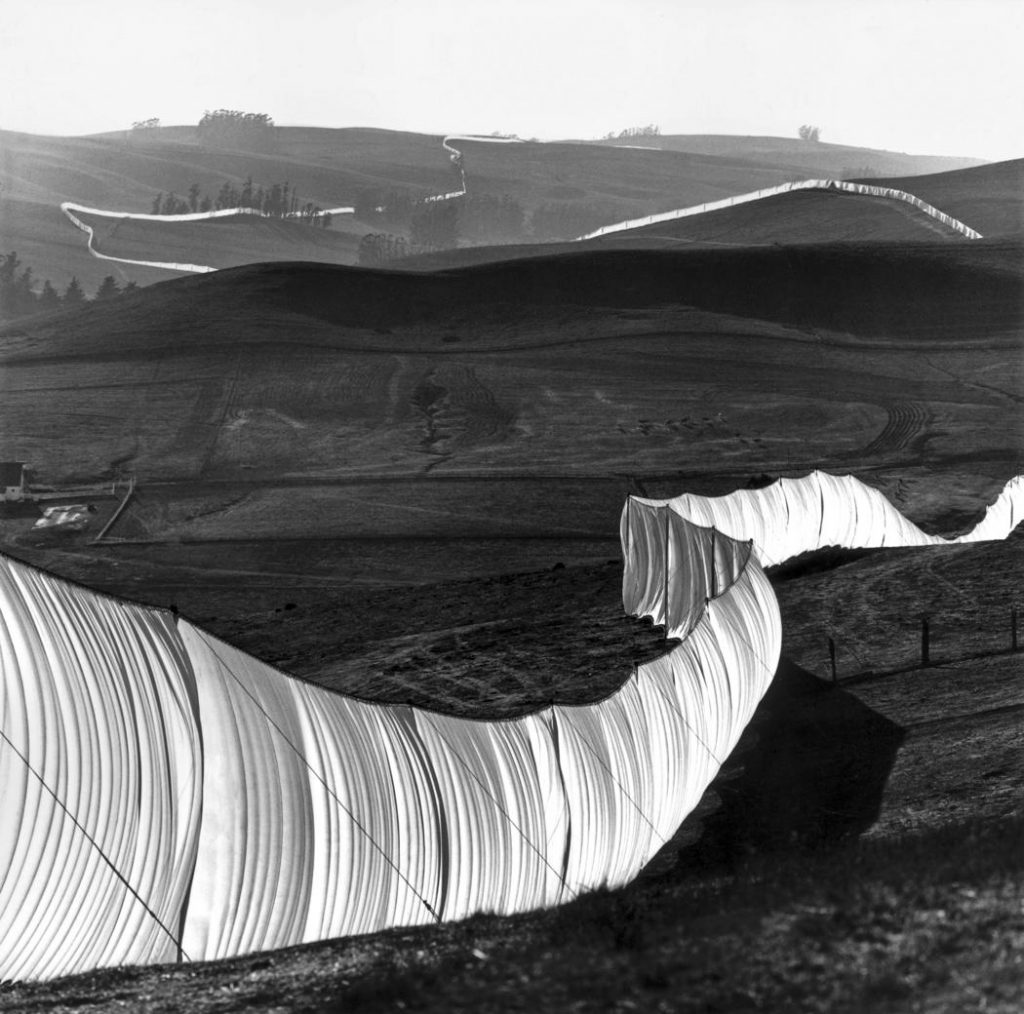

Man creates inside and outside himself limits, generating boundaries and barriers at the end of his portion of world.

Architecture is the fruit of this primordial act, similar to the individualist creation of a child, in the all-human attempt to relate (and often impose) to a natural space devoid of human signs which recognizing in with the need to find protection, his own nest.

Assuming the space as least common multiple of architecture and delimiting it – even if only symbolically – he creates an interior an an exterior, a finite and an infinite. Greek culture is very clear about this: the limitation is the key to knowledge and representation.

The usable is necessarily measurable, the attemtable verifiable, the assessable quantifiable.

In this sense, to paraphrase Geoffrey Scott, architecture derives from the need to protect oneself, isolating a convenient space by detaching it from the rest of variable and dangerous space through a construction.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude – Running Fence, Sonoma and Marin Counties, California, 1972-76

Is this the only matter? A self-constraint in a cell as isolated as possible from the surrounding, in the continuous attempt to eliminate the variables and changes that life brings as its intrinsic substance?

Architecture, and all its superstructures, is not only a means to exploit space and meet the needs of shelter but also something more. It is a continuous drawing of human living, or a design of the man’s constant need to live in the places, whether natural or artificial, which are always reproduction, description of the very first place.

Even when tampered, the world is there full of all its components and the argued, materialized effects, made possible by and in the material, are nothing different than approaching the cave.

Andrea Staid in his essay “Abitare Illegale” explains this inevitable consequence of human existence «The house is first and foremost an anthropological place, a place inhabited by man that is not only a “staying” but above all a “being»(1)

The spaces we live change and evolve with the same speed as we do so, they are a continuous reflection of our person.

The mutability of our soul, our aspirations and hopes, our values: all this continuously affects the spaces we coexist with.

The form is meaning. The form is essence. “Living” as Ivan Illich writes in “Volontà” «is one of the main characteristics of man. The home is the human place per excellence. Living and dwelling are synonymous in many languages. Ask someone where do he/she lives? It is in truth as asking to know the place where daily activity take place, what gives shape to the world»(2)

To simplify the understanding of this radical, but at the same time fleeting, elusive and multifaceted concept, it is perhaps useful to face it with three different, albeit interdependent, views or tools. The act of living, in all its complexity, shows and defines the relationship that man undertakes towards himself, towards a community of men and a geo-biological environment, of which he is constantly body and part.

Intervening and modifying the natural landscape – often compromising it – is an expression of a human need that in its nomadic origin did not exist: to attribute meaning and purposes to the material. The man becoming settled has tied his habits to his dwellings, building a habit of habits.

Michael Wolf -Architecture of density 2011

Fear, hunger and all that concerns his most ancient and never lost original component, what binds him to the intrinsically place which makes him a dependent on nature he assiduously tries to free from,; in the search for emancipation, he begins to know, he frees himself from the body to inhabit his head, he takes refuge in the highest cave on the tower. which then becomes a skyscraper he redesign his stages from and he measures the whole world.

And in the meantime everything becomes a burden, it needs refined technology to overcome the barriers that he himself builds.

As an animal without instincts, man appears to be the product of his subjective experiences. «Housing forges habits. living, clothes, habits are words not by chance linked by a common etymological root» (3), writes Adriano Favole. But living also has to do with another root that is deeply rooted in man: having a sense of ownership.

Man is a chain, he is not on top, but on a par with every other component. Man migrates between birth and death. It appears. It disappears. For this reason, to recognizing he needs symbols that represent him, whether objects, ideas or people, but also spaces and architecture.

Creating his own messages, and in this sense architecture influences the shape, he acts as negative – positive which man is connected to in a direct current.

Man takes charge of himself becoming a mirror that reflects the previous man, helping him to read clearly, in a continuous, collective man. But in what spaces are we willing to live? Are we aware of our connection with them? How do they bind us, enrich us, continually put us to the test? What does it mean to grow anthropologically in buildings like “Vele” of Scampia or in BedZed in London?

Ashley Cooper – Beddington Zero Energy Development 2002

Salvatore Laporta – Lightrocket 2016

If only it was enough for the man to enclose a space to protect himself, ripping his small part from the Earth, as G. Scott maintains, it would make no more sense to ask these questions.

The architecture, once this primary task had been exhausted, would have reached its goal. Maybe it’s not so, maybe it’s not that simple. Our way of building manifests our way of living together. It is the capacity of the human community to live and create functional, authentic, or alienated and toxic spaces.

Designing spaces, at an urban level, or at small scales, means influencing and intruding enormously on personal behavior. The psycho-physical influence exerted by the spaces can push us, within a community, to be different individuals – and hopefully better: more tolerant, inclusive, less alienated.

We only exist in relation to other individuals, we are the (and part of) eco system, and it is somehow the external recognition of our person to define our identity. The need to propose ourselves and manifest ourselves as social animals is expressed in living, «a difficult compromise between the need for intimacy and sharing and that of opening up to the world outside: a precarious point of balance between closure and openness , between the recollection in the intimacy of a “we” or an “I” and the opening to the social relationship» (4). [Francesco Remotti]

Architecture is a continuous dialogue between individuals of different generations, it reaches us through stratifications of signs and artifacts from the past, forging the personal and collective point of view determines the identity of individuals close to us, throwing themselves into branches beyond any of our measurements. It often exposes the dominant ideology, explicit the economic logic of the time. There is no exemption from these influences.

Architecture is also made of matter, it is defined by real spaces, which extend (but do not end) in the three dimensions, is a continuous contact with the environment, even in its most natural sense; every space we inhabit, whether it is a house or a collective and community space, is not only characterized by a comparison with the historical-cultural aspect characterizing the place itself, but also and above all by a continuous and punctual adaptation to the territory from the point of geological and geographical view.

Construction methods and techniques are the main expression, as well as the most tangible nuance of the act of living.

Each construction is a manifestation of an ideology, of an idea that becomes lògos: a will, a more or less partial adhesion to socio-economic policies of the time we live.

This is why it is so radically different to live, and choose, a self-sufficient house in sustainable materials compared to a popular building from the 1960s in concrete. If architectures are like clothes we wear.

If they adapt to our forms and are a visible sign of our being: we cannot leave them at the mercy others’ will, in the hands of presumed experts. But can we choose who to be and manifest it? What footprint can we or must we leave on the planet and among ourselves with our buildings?

We have the courage to make our spaces free and welcoming, to move away «from the asphalt of the roads and the elevation of cranes and the noise of the engines and the untidy interweaving of vehicles» which, according to Adriano Olivetti, are so reminiscent of a «vast, dynamic, deafening, hostile prison from which one must, sooner or later, escape» (5)

How many compromises are we willing to go down for convenience, conformity, a sense of security? But what security? To whom do we delegate our freedom and identity? When we also build a living fabric that connects us not only intermittently, but in a way that collaborates with each other: all species in a system as it already is.

Without wasting, without waste, without abuse, without domination, without possession? When we achieve a collectively bold cohabitation that we do not yet find, unlike mycelia – the lowest species but our common ancestor – who have already developed a prosperous life in interdependence with a moving care that continues to teach us and ask questions. Among us the “high” species that we should safeguard the “others” even if, now destroyers – perhaps – we do not deserve this wealth.

Bibliografy:

1 Andrea Staid, Abitare Illegale, p.20, Milieu edizioni, Milano, 2017

2 Ivan Illich, Volontà, p.16, Milano

3 Adriano Favole, Le case dell’uomo, Abitare il mondo, p.44, UTET, Milano, 2016

4 Francesco Remotti, Le case dell’uomo, Abitare il mondo, p.44, UTET, Milano, 2016

5 Adriano Olivetti, Città dell’uomo, p.78, Comunità Editrice, Roma/Ivrea, 2015