Among the most precious writings on the history of the Sassi of Matera stands, without a doubt, the work of Pietro Laureano Gardens of Stone. It is a treasure trove of reflections, historical events and comparisons with other timeless settlements around the world. The book is an ode to interrogate matter, history, myth, to the point of perceiving its majestic (perhaps unique) essence.

“A symbol of the conflict between tradition and modernity, an example for a sustainable city, a metaphor for a new model and a proposal for the entire planet” – as described by the architect of Lucan origin – Matera is the city that, with commitment and perseverance, transformed difficulties and poverty into a resource that since 1993 has marked its rise to wonder of the world, and UNESCO heritage site.

Pier Paolo Pasolini defined it as a place of the soul, and filmed his Gospel according to Matthew in the alleys of the Sassi.

Song of the earth, song of the stone

In the eighties of last century, in a fervent climate of rediscovery of peasant culture, Cosmo Francesco Ruppi affirmed that stones are to be considered the real books of history. We can start from this reflection to understand in detail the anthropic-environmental history of the stone age civilization of the ravines, without stopping at a mere superficial view of the buildings that mark this path.

Matera, an ancient “troglodyte city”, owes its urbanization to the succession of particular geological, geographical, political and economic factors, combined with the great tenacity of the populations who have inhabited it over the centuries. The first appearance of the term “Sassi” is found in a document dated 1204, to indicate the stone districts that make the historic center.

The Civita Hill was the first settlement of the city, sat above two natural amphitheaters, which over time became identified with the city districts known as Sasso Caveoso and Sasso Barisano.

The two valleys, characterized by the mighty presence of caves in the porous rocks, over the centuries have seen the labyrinthine intertwining of houses, alleys, churches, hypogea and hanging gardens.

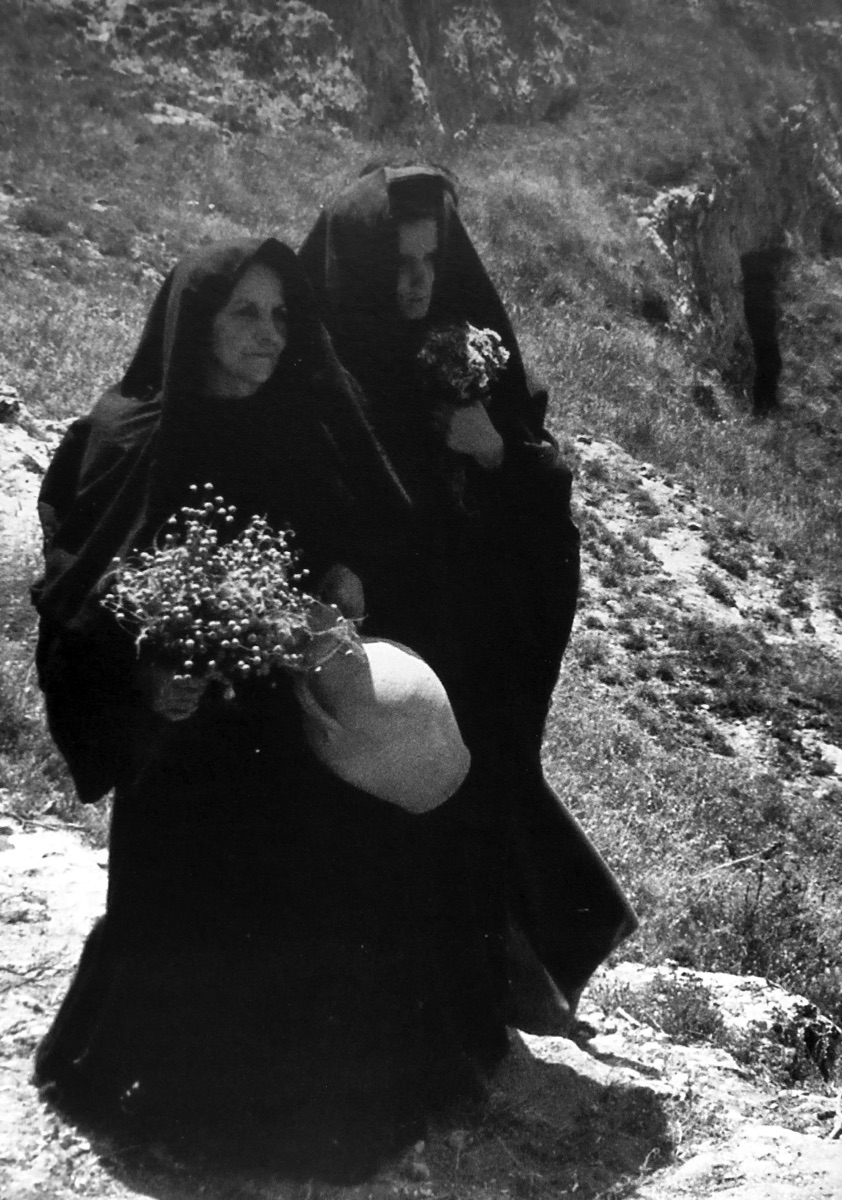

©Notarangelo Archives; from Pasolini’s set of The Gospel According to Matthew

Rock House

As accurately written by Fernando Ladiana:

The houses consisted, for the most part, of one or two rooms, not too large, sometimes equipped with a monolithic dividing wall, to separate the living room and kitchen from the bedroom. Occasionally there were houses with the typical alcove (still found today in the old masonry houses in Massafra), divided by a central pillar with round arches. The ceiling was always flat and the height of the floor was just over two and a half meters. The hearths (some with hoods, others with a simple fireplace) were almost always on the left side, right after the entrance. There were numerous niches for housing the family presses (used for pressing grapes) and containers for storing wine, oil, honey… Other simpler smaller niches were used to store water containers. The walls and ceilings had holes and hooks used for bedding and for wooden shelves on which dairy products and sausages were placed. They were also used to suspend the lamps and, if necessary, a cradle of the newborn, made of a burlap sack or woven cloth.

In some caves there was also a manger, but it is believed that this structure appeared in more recent times. Stables, chicken coops, rabbit hutches and beehives were created outside, in shelters under the rock, preferably exposed to the air and the action of sunlight.

Regarding the caves intended for work activities:

Warehouses and deposits had large circular tanks inside with the opening equipped with a ring to close it. Rather than water deposits, today they are thought to be silos for storing cereals and beans products. Some rooms had pits, basins, drainage channels and collection piles.

Few houses had a small window; doors and windows had gutters, made with a lunette dug channel. The waters were collected in special drains on the sides of the entrance door

It is important to point out that this description does not constitute a prescriptive housing rule, as each house responded to the most practical needs of its own inhabitant-builder.

In fact, as claimed by Laureano:

In ancient Matera, the balance between consumption and materials is always maintained. The buildings, an external projection of the excavation work, are the emanation of a profound principle that locally regulates any exchange of energy and creates an intimate encounter between men, animals, plants and matter. In the past every mood, every ejection, every waste of time was constantly used, and the most remote memory remained present in the underground bowels.

Today the empty shell and the underground volumes, the positive abandoned and the negative removed from the Sassi, remind us how everything has a price in the environment, and that each creation corresponds to a hidden molded shape

©Notarangelo Archives; Susanna Colussi, Pasolini’s mother, played Madonna’s character

In the Garden of the Origins. The Cult of Life and Death

In Matera saints and anchorites have created gardens of aromas and medicines, and since they lived underground they dug graves on their heads. So while among the Egyptians, in Petra… the city of life separates from that of the eternal residence, in the Sassi the tombs are not in deep darkness, but out in the sun of the hanging gardens:

“The dead stand above the living”

The cemeteries carved in the limestone are very popular and they are similar to the Neolithic garden burials: where vegetation grew with more intense color and luxuriant forms; front yards/altars to celebrate the mandatory law of sacrifice, stone gardens where the fertilizing power of decomposition was learned

Laureano offers poetry to the description of the hanging gardens typical of Lucania and of the land of the ravines, retracing the mythological tradition that still accompanies the alleys and houses of that rare stone, because it is eternal. That is why, even the choice and existence of some planning and urban architecture methodologies, seems to have responded and maintained over time the closest link with the myth and the merging of the most disparate cultural contributions.

In this regard, it should be remembered that, boasting a millenary history that has roots in the Neolithic era, Matera has seen the passage and coexistence of people from distant lands. A large part of the myth that characterizes the town originates in the contribution of the people of the Mediterranean basin; it is also true that, as asserted by Aldo Tavolaro:

[…] everything is mixed with ancient civilization, with things thought and studied, flowed here from various channels, screened and acquired by our ancestors endowed with doctrine, taste and sensitivity, but what is more important, open to all knowledge because for them knowledge did not admit borders. And from the same rulers and invaders with the abuses they also took all that was good and useful, reworking it with intelligence and without hostility.

Going back to the words of Pietro Laureano:

Surrounded, like the goddess Kalì […] Matera, with a thousand arms of stone, is the union of life and death, a fossil body and palpitating flesh. Mater materiae, a meteor, a starry sky, underworld and cosmos together. It is the meeting of space, time and matter with its reverse side.

[…] In the fossil body of this theater of the world, where the difference between stages and scenes disappears, actors and spectators, where all ages are contemporary, the stone gardens flourish, life returns to represent a millenary human story.

The Sassi tune the song of the Earth

Mater Era, mother of the Earth and the gods

As always with a mythical aura, Laureano describes a precious and extremely crucial document now preserved in the Angelica Library in Rome. It is a 16th-century map, where the drawing of the Sasso Barisano recalls the female sex in its shape. In this regard, the scholar traces one of the most ancient and possible etymologies of Matera, assuming that it can be linked to the root MTR, present in African languages precisely with the meaning of the primordial matrix, the vulva. Here lies the great and mysterious vision of Mother Nature from which everything begins and to which everything inexorably returns, in the cradle of eternity.

[…] The lips on the edge of the Murge jagged by caves that surround a central crack furrowed by the grabiglione. Here, at the center of this curious map, which represents the fountains, the lake of the city, the castle and the most important churches with realism, the inscription says:

“Map of Matera / The caves surround it like a theater”

Ancient map of Matera territory, XVI century. Rome, Angelica Library

Using other possible etymologies, the Lucan urban planner also includes Mater Era or Ea, mother of all gods and from which the term “aia” (or “barnyard”), as a fertile place, derives. The Divine mother was greatly venerated in Lucania, in the gardens of the sanctuaries where, as in Athens, the secrets of preparations and drugs were kept. It is believed that the care of seeds of various plants pertained to the loving care of women. Seeds were kept in the dark of the cellars so that in summer they could blossom, and be moved on the inhabited terraces, to be seen. The garden vases, reminiscent of the mostly dialectal term “graste”, in Athens, were known as small gardens of Adonis:

Similar to transportable gardens of the most distant prehistoric times, and lovingly cultivated by Eve, the “graste”, where wheat is sprouted in the darkness of the caves, are still in use in southern Italy and in particular in Matera, where they are brought on the altar during the ceremonies of Easter tombs as a symbol of devotion and faith in the resurrection

Matera rose like a phoenix from its own ashes, perhaps never ceasing to show to the roots of its story:

[…] You have never ceased to offer a blissful, original, and final dimension.

[…] (maternal) vision of a starry sky.

Place of the soul. Pasolini chooses Matera

In June 1964 Pier Paolo Pasolini arrived in Matera to shoot his Gospel according to Matthew. As Rocco Calandriello says:

Pasolini, speaking to the world, chooses the world: he chooses Matera. He finds in the Sassi the perfect colors for his intimate and universal designs, creating an indelible work in the vapors, in the humidity of the Sassi.

He anoints the Sassi of mercy and universal compassion.

The sets were set up in different parts of the city: in the Sassi there were two, the first in Barisano, between via Lombardi and via Fiorentini, the second one in the location of Porta Pistoia where, with some light material, the large arched door was rebuilt. It reproduced the entry of Christ into Jerusalem. In the neighborhood of the Sassi and along the stairs that go up the Caveoso, numerous extras were employed for the same scene in which they were waving olive branches.

As documented by Domenico Notarangelo:

Right there, in that place, one had the perception of being in a true and real Holy Land

[…] It was understandable why Pasolini had chosen to set much of his Gospel in Matera. He had, in fact, told the producer Alfredo Bini during a documentary he had made in the Holy Land […] Matera was a point of encounter and fusion between the Christian East and the Roman and pagan West. In the Sassi and on the Murgia San Vito, Pasolini discovered the places of the Gospel, not cramped and “bare”, but grandiose and majestic, biblical […] in the ancient districts of Matera, where the underclass still lived, alive and palpitating, the faces were like those Jesus had encountered in his wanderings

The last set concerned the crucifixion scene, on the Murgia beyond the ravine, between rocks and brushwood. A poignant landscape that looked right in front of the Sassi. Among the characters, the Madonna was played by Susanna Colussi, Pasolini’s mother. Notarangelo describes her:

A woman with a very sweet face, that on stage was contracted by immense pain. The director often retouched her with his own hands before the take. A gesture of infinite love

In 2011, the council chamber of the Municipality of Matera was named after Pasolini. This goal was achieved thanks to the great interest, always kept alive, of the Cultural Circle Pier Paolo Pasolini, created by Domenico Notarangelo and his sons Mario and Toni.

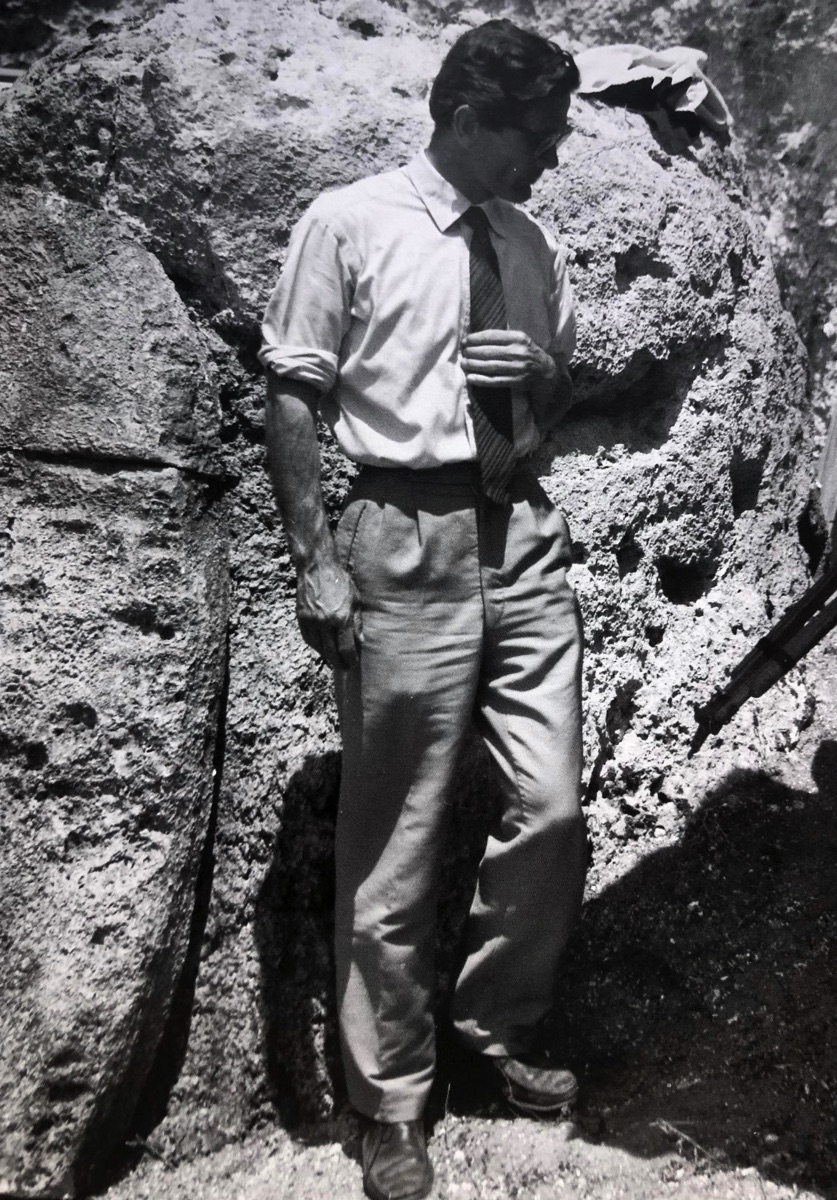

©Notarangelo Archives; Pasolini with his camera

Even Pasolini ate that bread. The memory of Domenico Notarangelo

[…] The Maestro wanted to meet me. The invitation filled me with pride. My knees were trembling with emotion, in front of me was a thin and polite, simple person who immediately put me at ease talking to me as if we were two friends who met by chance. My eyes moved from his black glasses to the tiny little tie knot

Domenico Notarangelo, born in Puglia, Lucan by adoption, was for many years correspondent for “L’Unità” and editor of various television stations. His passion for photography and his interest in the popular traditions of the South led him to collect hundreds of documents that now form one of the most important private archives in Southern Italy. During the summer of ’64, as told in the book Pasolini Matera, Notarangelo surprisingly found himself collaborating with Pier Paolo Pasolini. This opportunity allowed him to take snapshots of poetry about Pasolini the man, and the emotional charge of his Gospel.

As Paride Leporace tells us:

Notarangelo – I prefer to call him Mimì – was able to make the reproducibility of one of the greatest works of the twentieth century happen with his photographs, attaching it to the destiny and history of a World heritage site.

[…] The still photographer Angelo Novi, a long time photographer for Pasolini and other great Italian directors, has captured moments in the construction of the work. His are photos of cinéma vérité. Notarangelo, a film buff, Pasolini’s security organizer, was in charge of organizing the extras and was an extra himself. He hides his camera as a reporter and documents what is happening.

Feeling the weight of History, he immortalizes historical moments of that work, which is also made of pauses and thoughts

Notarangelo offers to history the image of the great intellectual without glasses intent on tinkering with the camera or still immersed in his thoughts, to the horizon. His frames are destabilizing icons, from which we infer the telling of the soul, which seems to infuse itself with images from the same thoughts and questions the writer has given to the future. Sepia, black and gray scales create metaphysical landscapes, in which we immerse ourselves, until we are lost.

Scenes and life merge in that great world of tuff and stone, drawing the enchanting urban line of Matera. The journalist’s curiosity and the hypertrophy of testimony, which will be well cultivated in the religion of memorial remembrance, will found the myth of Pasolini’s Matera, destined to become a cinematographic city

One of the shots stolen by Domenico Notarangelo was chosen by the Metrò la Cinémathèque in Paris, to advertise the exhibition in honor of the great director.

Pasolini believed in the uncontaminated Matera of the soul even before society recognized its merit and beauty.

©Notarangelo Archives; Pier Paolo Pasolini on his set

Special thanks go to the Notarangelo family for providing the necessary material for the research project. The text contains some of the photographs owned by the Notarangelo Archives, which the Ministry for Cultural Heritage has declared a heritage of national interest.

Bibliography

- P. Laureano, Giardini di Pietra. I Sassi di Matera e la civiltà mediterranea. Nuova edizione, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino 2018

- D. Notarangelo, Pasolini Matera, Edizioni Giannatelli, Matera 2014

- E. Caracciolo, Matera. La città dei Sassi, Ediciclo editore, Portogruaro 2014

- N. Bauer, C. Giacovelli, Un’ipotesi di lettura urbanistica e storica dell’antico casale di Basento, in “Riflessioni Umanesimo della Pietra”, Martina Franca, July 1981

- F. Ladiana, Lo sviluppo civile e religioso del vivere in grotta, in “Riflessioni Umanesimo della Pietra”, Martina Franca, July 1987

- A. Tavolaro, L’enigmatica Chiesa di Santa Maria di Basento, in “Riflessioni Umanesimo della Pietra”, Martina Franca, July 1987

- E. Di Salvo, Matera. Pietre preziose, in “Meridiani. Matera e Basilicata”, n.247, Anno XXXII, Rozzano, February-March 2019