The Italian territory, from North to South, preserves traces and precious testimonies of the human capacity to regenerate, cooperate and face the most difficult needs. Given the objectives set by the UN 2030 Agenda on sustainability, how to re-read the past? How to rediscover the simplest forms of life, essentially re-evaluating their beauty and authenticity?

In a small town located in the South-East of the Apulian capital, Sammichele di Bari, an ancient urban layout survives, the result of mastery and wisdom, which seems to recall that survival architecture defined by Yona Friedman: “the exceptional mother of social innovation.”

The characteristic aspect of this urban planning is constituted by the “Vignali”, modest rural houses in local stone.

The history of Vignali

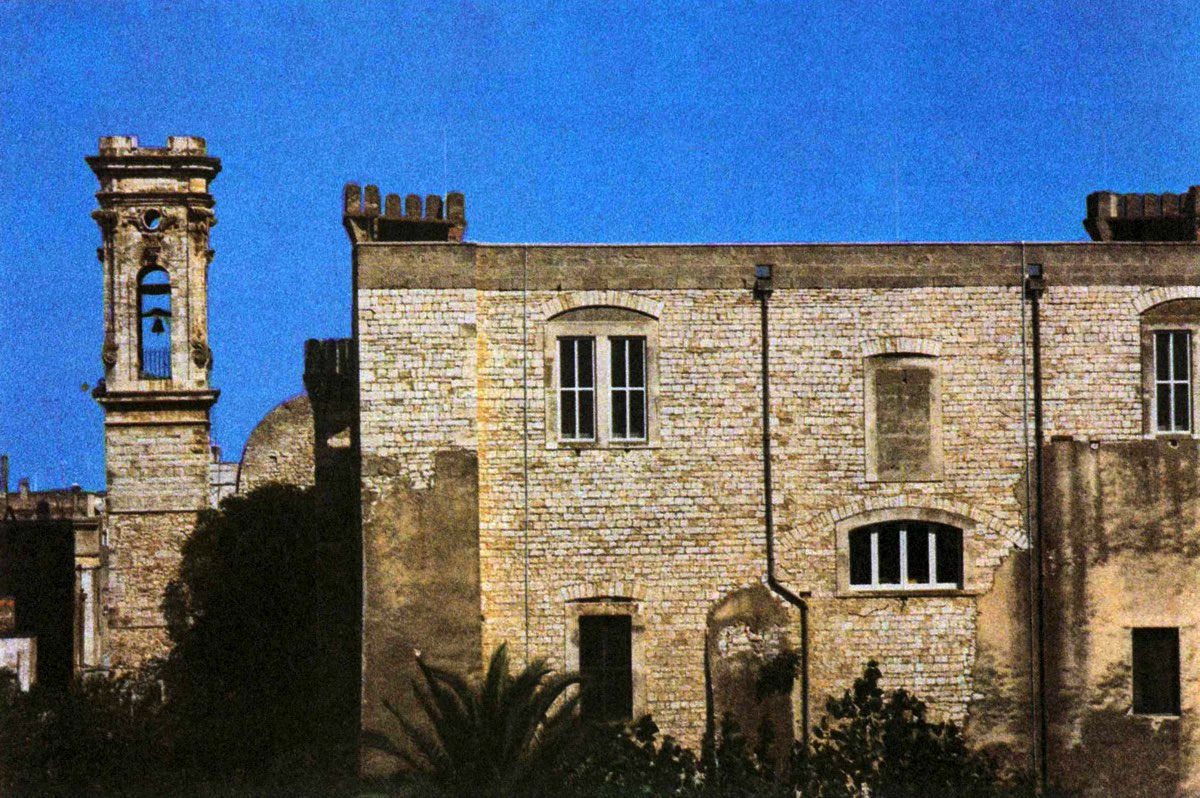

The origin of these buildings, as modest as they are resistant to the passage of time, finds its symbolic date in 1609, when the rich Portuguese merchant Michele Vaaz, bought the fief of Casamassima with adjoining territory from the last heirs of the Acquaviva D’Aragona family. surrounding the Centuriona Tower (name of the original structure incorporated in today’s Castello Caracciolo).

On 20 December 1609, the deed of purchase was drawn up in Naples and from 1615 Vaaz, having become Count of that territory, laid the foundations and the first urban planning rules for the foundation of the future Sammichele.

West view of the Caracciolo Castle © courtesy Archivio Antonio Deramo

We read on paper that the town must rise around the Centurion Castle and, for it to be built, a community is needed to settle there. Michele Vaaz thus sends his men to Cattaro and it is there that they come across a colony of Serbian refugees from the principality of Zuse, harassed by the Turkish invasions and therefore forced to take refuge on the Adriatic shores, where the Republic of Venice still opposes a bulwark against the Turks.

The negotiations are short, the colony of Serbs willingly accepts the transfer to Italy at the expense of the Count and after a few days, the troops disembark at the port of Barletta, headed by the priest Damiano de ‘Damianis of Cattaro. On 6 July 1615, a Serbian representation arrives in Naples where the notary Vincenzo de Troianis draws up the contract for the foundation of the new village. The stipulation provided that the new inhabitants, of Orthodox religion, would marry the Catholic rite, as well as the construction of 87 residences around the castle, called “vignali” precisely because the custom would have been to plant a vine branch on the door of the main entrance.

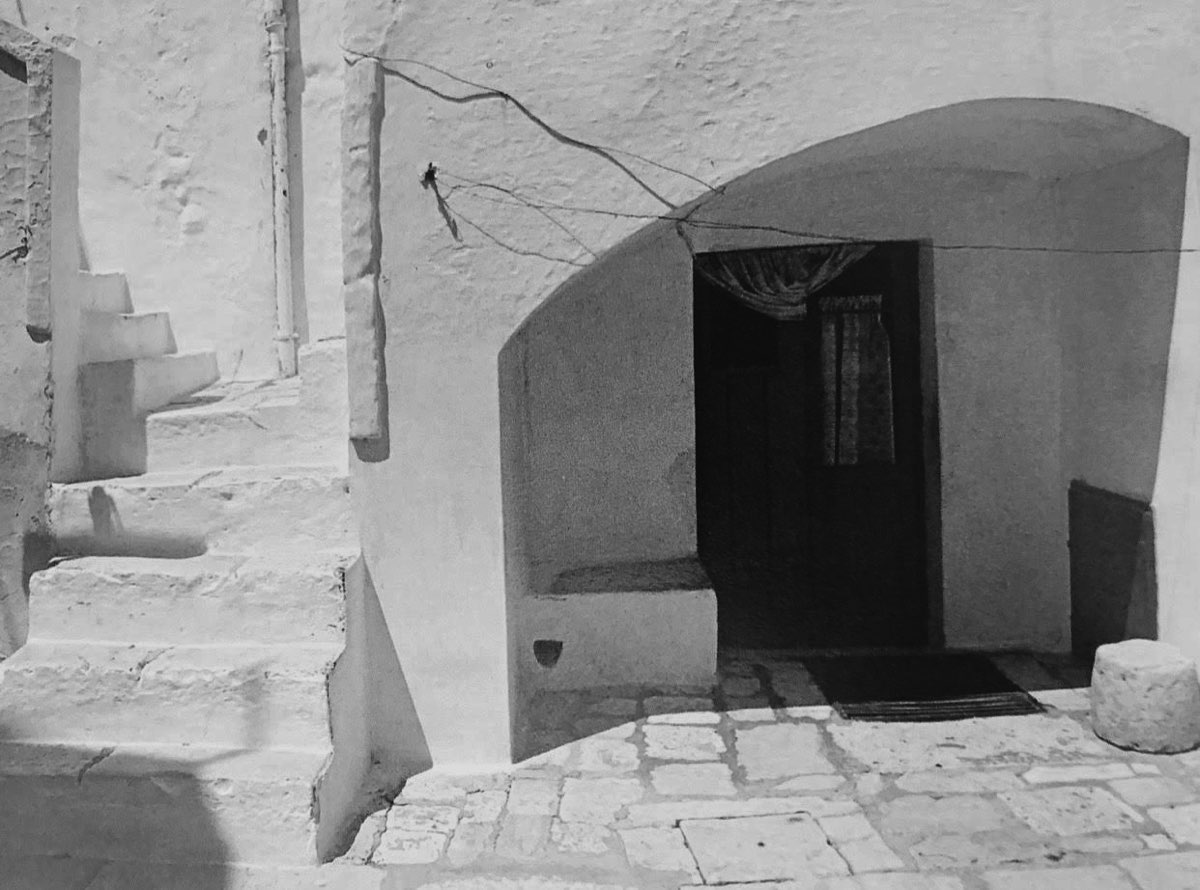

Vignale with vine branch © courtesy Antonio Deramo Archive

The plant was carefully pruned for this purpose, thus forming over time an intertwining of the branches that offered decoration and shade. The use of the vine to cool the sunny doors has continued over time, still finding wide use in the typical stone houses of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Two-storey Vignale © courtesy Antonio Deramo Archive

On the doorstep: the vine between utility and urban decoration

Symbol of truth, well-being and protection, the vine plant seems to frequently accompany the Mediterranean tradition. If there are countless Greco-Latin documents of the presence of its fruit at the most succulent and famous banquets, the bas-reliefs of the marvelous Romanesque basilicas and Gothic cathedrals, hosting episodes in which the plant is the protagonist, are equally well-known. Indeed, following the Christian symbolism, the vine represents both devotion and protection from all evil.

From a symbolic point of view, according to the testimonies and stories of the peasant world, the vignali are also part of this tradition.

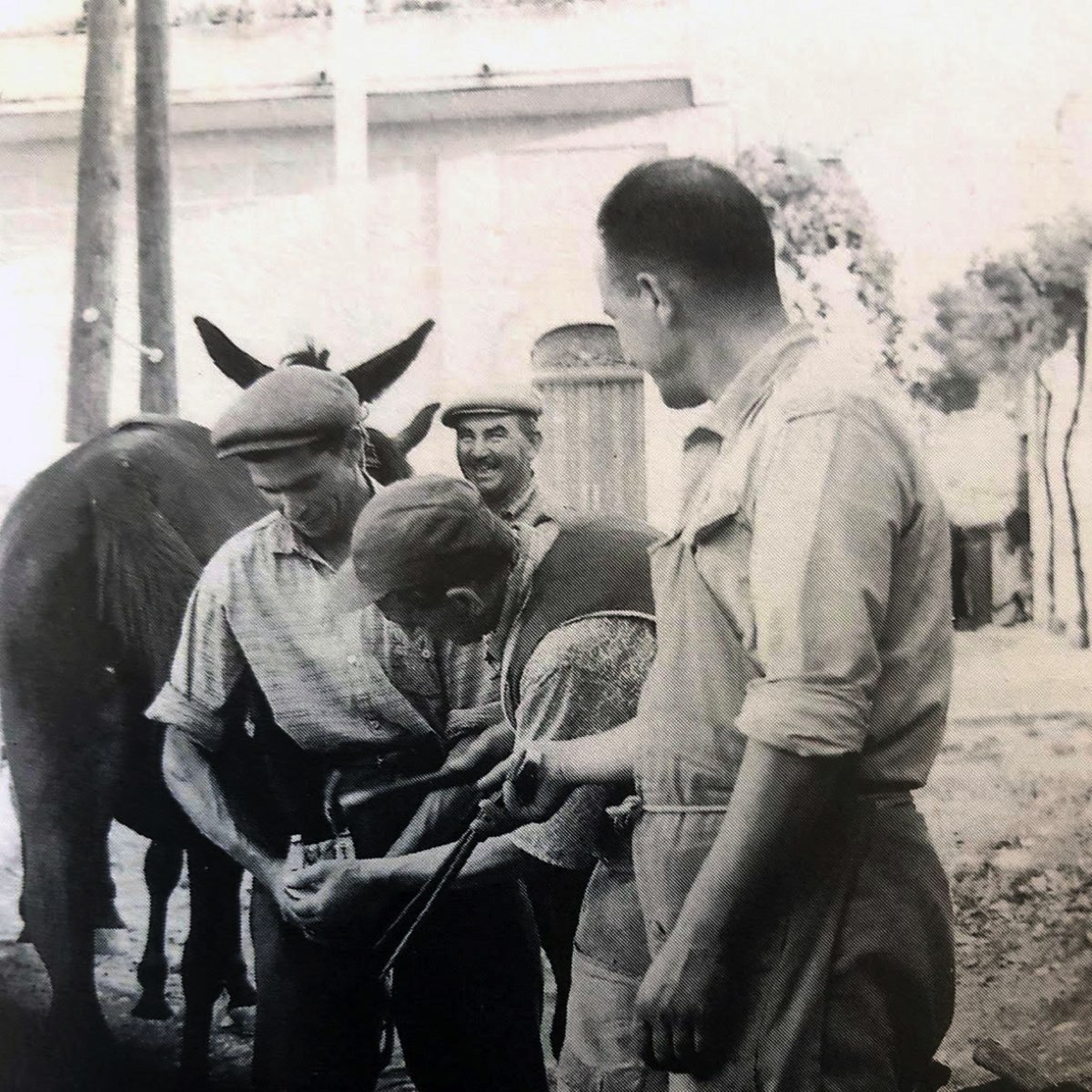

Domestic life scenes © courtesy Domenico Notarangelo Archive

A forerunner of the master plan

“[…] una casa terranea a lamia di pietra viva con focolai, porte finestre et altre comodità necessarie, coperte da imbrici, quale predette case ascendono sino ad oggi al numero di ottantasette ultra la quale esso sig. Conte si obbliga a fabbricare altre tridece che siano tutte al numero di cento”

As it is possible to learn from the foundation contract of 1615, the design and construction of the houses immediately respond to a real master plan with relative indices. This is a fundamental aspect if we want to compare the experience of the foundation of the new village with that of older rural centers, which at the time of the city structure already had a constellation of small inhabited agglomerations, structurally and aesthetically different from each other.

Domestic life scenes © courtesy Domenico Notarangelo Archive

Strolling through the alleys

Even today, wandering through the narrow streets of the historic center, in the Casamicciola district (east side of the Caracciolo Castle) or in the historic streets such as Vico Spezzato, it is possible to see examples of ancient Vignali. Sometimes there is still a fragile but resistant branch of vine to accompany them, while others still characterize them the part of a curtain, carefully sewn by hand.

In Diaz Street, a few steps from the Castle, two-storey Vignali dominate, where each arch of the entrance to the lower floor of the house is punctually accompanied by a stone staircase leading to the upper floor. Indeed, following the sovereign rule of every typical peasant dwelling, nothing had to be lost and therefore what functionally allowed access to the upper floor (the staircase), in turn, served as a cover for the floor below.

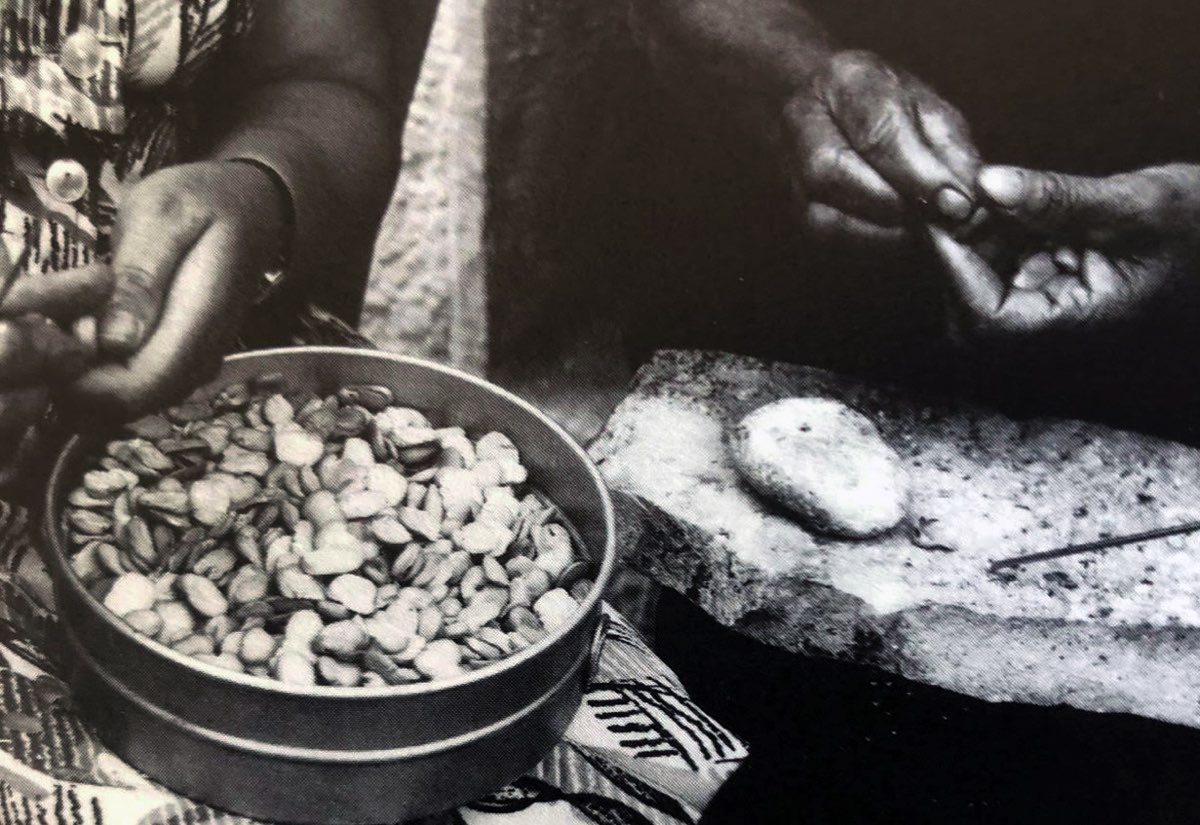

In Vico Spezzato, the eye is drawn to a Vignale under whose entrance arch to the lower compartment a small block was built that served as both a seat and a shelf for food. In the warm seasons, when domestic activities were carried out mostly outdoors, these rustic accessory additions were used for tasks, such as cleaning the beans, that inside the house would have caused an excessive waste of waste and dust.

Vignale of Vico Spezzato © courtesy Antonio Deramo Archive

The (re) discovery of poverty for a sustainable world

In an ever-current essay, Friedman affirms that poverty needs to “be discovered concretely and rediscovered periodically because it does not manifest itself in the same way in the various epochs”. Today, every inhabitant of the globe should consciously realize that there is a poverty that sees everyone participating: that deriving from the now established certainty that environmental resources, previously believed to be unlimited, will soon no longer be sufficient for everyone. This involves the abandonment of any possible positivistic and progressive vision (leitmotiv in the era of industrialization), in the name of self-planning and an increasingly careful safeguard of the environment. Starting today from small villages, perhaps never really overwhelmed by the wind of innovation of big cities, means rediscovering simple life mechanisms that for a long time we have set aside in a sentimental corner of our existence, still considering them significant, but now overcome.

Domestic life scenes © courtesy Francesco Cici Archive

In the flow of a continuous return, we hear more and more often about new (?) projects aimed at introducing city experiences of self-production of resources (such as fruit and vegetables; just think of zero-kilometer city initiatives) or even insertion of greenery in the most avant-garde constructions of the great world metropolises (our thoughts go to the marvelous vertical gardens), but perhaps what we are planning is nothing more than a loving reverie (in the Bachelardian meaning) of that great and humble ancient world that relives in us. Characterized by persistence. Motivated by respectful wisdom.

Domestic life scenes © courtesy Domenico Notarangelo Archive

Bibliographical references

- Friedman, L’architettura di sopravvivenza. Una filosofia della povertà, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino 2003.

- Boscia, G. Trizio, L. Netti, Un territorio una cultura: dalle origini a San Michele di Bari, Sammichele di Bari, SUMA Editore, 1985.

- Notarangelo, San Michele e Sammichele. La cultura dell’appartenenza, Schena Editore, Fasano 1999.

- Larocca, Note storiche e sviluppo cronologico delle vicende religiose e civili di Sammichele di Bari, Arti grafiche Angelini & Pace, Locorotondo 1958.

- Giacomo Spinelli, La Centuriona. Una torre nel territorio delle Quattro Miglia, Sammichele di Bari, Ideal Stampa, 2013.

- Bachelard, La poetica dello spazio, Edizioni Dedalo, Bari 2006.

The photographs shown are archive repertoire; Domenico Notarangelo Archive, Francesco Cici Archive, Antonio Deramo Archive.